Home

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty

Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

GESLOTEN / CLOSED

16 okt - 5 nov '25

Contact:

31-20 - 6 23 55 64

06 - 588 41 370

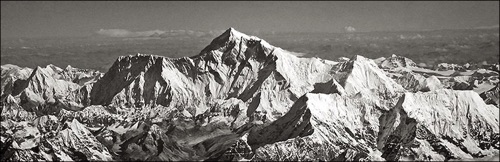

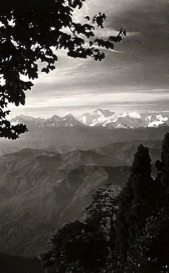

Winter 1729. Along with Giovanni, Samuel climbs one of the highest mountain peaks around the valley called Nepal early in the morning.

Overnight fog filled the valley to the rim but is already slowly dissolving. An eagerly awaited little sun starts battling the damp chill.

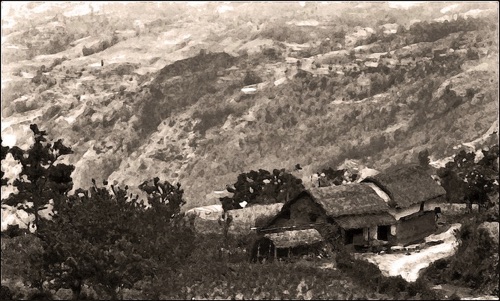

With their heavy kapok blankets still over their shoulders, families of farmers warm themselves in courtyards or on roofs in the first skimming light.

In the bazaar of Kathmandu, Samuel got himself a sleeveless vest of beaten yak wool. Underneath, he has a shirt with strings and a pair of brushed cotton trousers. But it is the exertion that warms him somewhat.

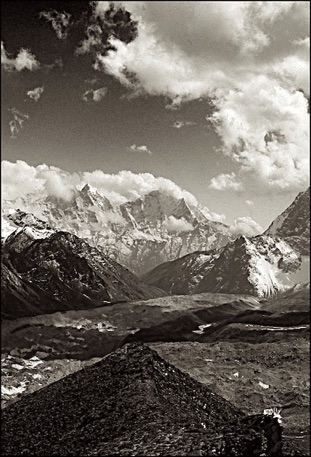

After a steep climb of several hours, the two men silently gaze across the valley to the snowy mountain peaks on the horizon. How could he ever sketch that grand, majestic sight to friends and family, most of whom never even leave Vlissingen.

He has been here for a few months by now but still understands little of the world below him.

In all, it will certainly not be larger than his home island of Walcheren, he estimates. Yet, at least five faiths mingle and it is ruled by no less than three kings – apart from remote hilltop

villages with their own village chiefs or landlords.

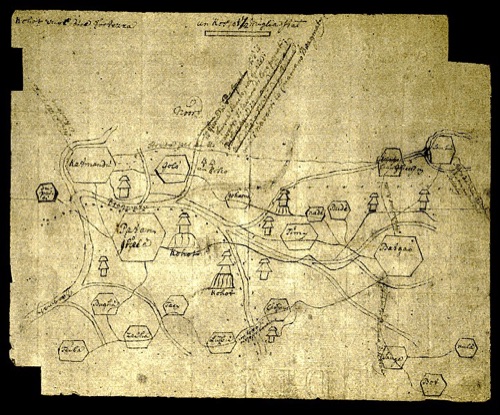

That is why he came up with the idea of mapping the area. Since his inspiring encounter with padre Desideri in Patna, he has increasingly been writing and drawing in his giornale.

Without the help of Giovanni, however, he would not succeed. Not only does the young Newari know the valley inside out, he has been translating for the capuchins and benedictines from Newari to Italian and vice versa for several years now.

'Un giovane di buon intelletto,' Samuel scribbles between his notes. He considers him 'ingenious and the most capable man I could find to draw a map of his land.’

By getting baptized, Giovanni became as much an outsider as the European mendicants, but in the end that is not a lot different from the caste in which he was born. Giovanni is too ingenioso for the many restrictions that the caste system imposes upon him.

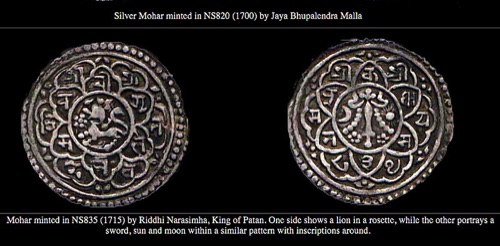

Centuries ago, he explains to Samuel, a Malla king divided the valley between his three sons. Right from the start they harassed and fought each other and then their sons and their sons - the infighting has been going on ever since.

Except during a few important religious ceremonies when all the descendants have to come together to reaffirm their ‘god-given’ power – and are certain to be able to leave alive and well.

The periods that the Malla kings do not fight among themselves are rather sparse over the centuries.

Usually the soldiers simply remain in position. The young men are recruited among the peoples in the promontory and selected for

their physical strength. They are poor, propertyless and uneducated, but do realize that sooner or later they will lose their lives.

Kings and priests assure them, however, that they will no doubt fare so much better in their next lives.

There are frequent virus outbreaks. Diseases such as dysentery, jaundice and smallpox deplete the population.

Less than ten years before Samuel's arrival, over a hundred inhabitants die daily in each of the three capitals.

Among the freely roaming animals mortality runs high as well. Only between the fields is there less misery.

Inflammations, diarrhea and other diseases have made Samuel extremely careful with food and drink.

Smelling and sniffing he first tried to check what it was exactly, where it came from and who had prepared it.

From his family as well as during his studies in Leiden, he did acquire some learning about medicine and drugs, but all that knowledge by now had been eclipsed by what he had seen and comprehended during his journey.

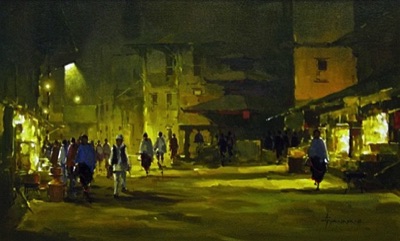

On his way to the city he notices farmers not taking the small bridge, but wading through the river and lowering the yoke with their baskets into the water. So that the vegetables will look clean and fresh on the market.

But this is the very river where he sees many villagers doing their morning shit, while dogs and pigs wait around to

One night he had spotted the small bright eyes of hyenas, which explained the half-eaten carcasses of animals and the circling vultures in the air.

In some back alleys he sees how the throats of goats and water buffaloes are sliced and smells how their hair and skins are scorched.

No caste mixes with the butchers’ caste, but nearly all eat the meat they sell. As long as someone else does the killing, the meat is apparently karma-free to consume.

With a similar contempt as the villagers’ attitude to the low-caste butchers, the latter seem to treat the animals.

Chopped-off legs in front of the hut indicate what kind of meat is being sold that day - if they are still visible through

the clouds of big black flies.

Consequently, it is not always the crown prince succeeding the king. Sometimes only women with small children are left in the palace.

At such a critical moment in one of the Malla monarchies, none of the other kings is above observing the honours for a while or hoisting woman or child onto the throne and placing the ceremonial red dot on one of their foreheads.

Only to resume skirmishes as usual upon returning.

Sometimes Samuel watches a monarch pass by on the street, on his way to a ceremonial obligation, minister or concubine. Then it seems as if the ruler is concerned with his people - and they with him.

He dutifully fulfils his traditional role in the temple and during public ceremonies, but if desired he shows up at home with his subjects as well – at birth, marriage or death.

One day Padre Freyer sees a fleeing felon desperately holding unto the wall of the palace, knowing that no one can harm him there.

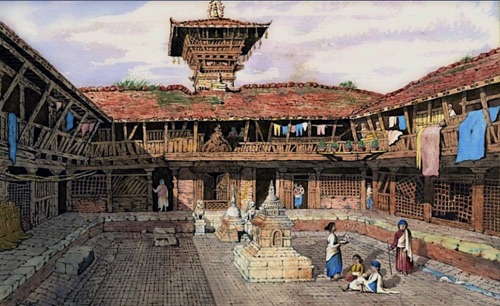

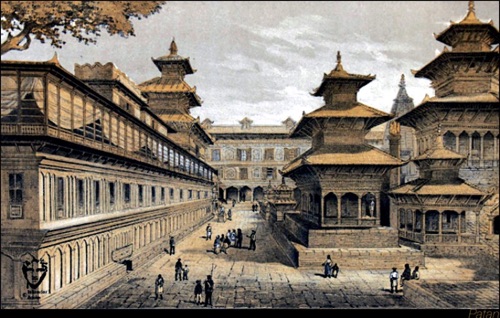

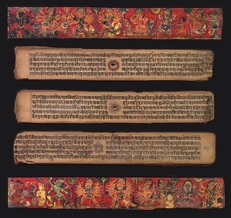

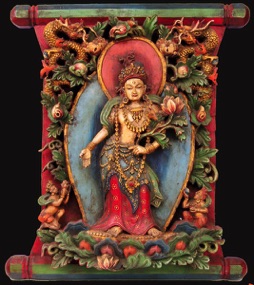

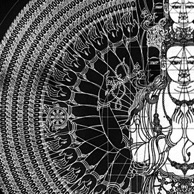

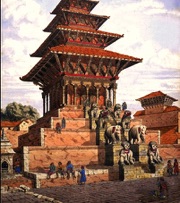

Srinivas Malla, king of Bhatgoan, wanted the people - and especially his ministers - to believe that he was a manifestation of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara. The window of

his palace, from which he daily looked out, he had decorated with the necessary iconography (guards & carriers) and symbols (mala, lotus, etcetera).

The fact that according to one of the most important Newarese writings all brahmin gods - from which the priests and ministers partly derive their position

- emanate from Avalokitesvara, was coincidental, of course.

Bravado, daredevilry, bragging, boldness – such terms characterize the centuries-long Malla dynasty.

Yet, the peasants - who had to pay a great deal of royalties with hard work - do not hesitate to speak up to their passing monarch and offer some advice.

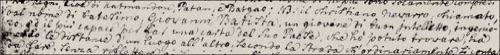

A few years before Samuel's arrival, the king of Bhatgaon invited his subjects to a courtyard

of the palace to vent their grievances. Already for a while the people had been angry because he openly preferred one of his concubines, living in another village, in stead of the queen. Both women had a son with him - the people sensed bad weather coming.

After working the land, while dusk was falling, the meeting took place inside the palace walls.

Nevertheless, the farmers dared to cry out their grievances against the prominent company on stage loud and clear - albeit with twisted voices and hidden by scarfs or cloths.

One of the capuchins attends and describes how the monarch listens in silence - what other

choice does he have. But only for the priests and ministers next to him is it threatening, he himself being a heavenly manifestation.

You may force farm workers to their knees in the wet clay from dawn to dusk, yet there are limits. The godsons that went too far, were chased out of the valley.

Occasionally the catholic enclave was requested to come and mediate – but the capuchins wisely declined.

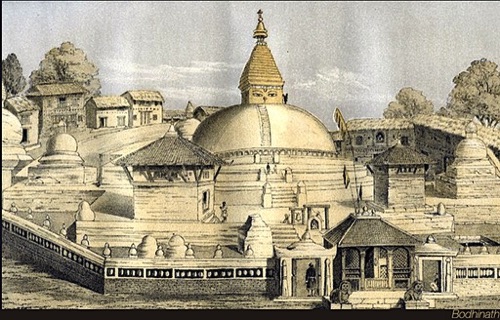

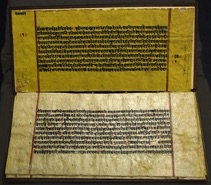

The valley itself did have a few small monasteries, but most students and scholars left for the large monastic universities in Bihar or further into India.

With the help of old Sanskrit texts the crown princes were trained in, for example, the handling of (state) conflicts. In particular, in the diplomatic approach according to the four Upayas:

1. talk, explain and mediate (sama)

2. offer an alternative or compensation (dana)

3. impose coercion or punishment (danda)

4. negotiate treaties with third parties (beda)

Clearly, priests and other high castes were familiar with hindu and buddhist scriptures.

Thanks to the trade routes, they only knew too well that an outside world existed where their own knowledge, glory and traditions paled to insignificance.

Nevertheless – but usually deliberately – the valley remained a fairly closed small world for centuries.

Traditionally, the rulers often entertained a small harem. Even though he could only choose from the higher and therefore usually wealthy castes, being chosen yielded plenty of other than merely financial advantages for a concubine and her family as well.

Jaya Prakash Malla, for example, had the annual procession chariot, carrying the village maiden Kumari, make an extra tour so that his favourite courtesan could watch the procession from her own house.

(Since then, the Kumari festival takes an extra day.)

Whatever the number of mistresses, all possible prestige and respect goes to the first wife. As soon as the king dies, however, all distinctions are gone and all the women must accompany his corpse on the pyre.

Surely, no 'virtuous woman' (suttee) will want to live any longer than her husband. Consequently, the children, including the heir to the throne, often lost both parents at the same time.

During such dramatic changes of power life in the valley stopped, the burning of widows was not commonplace.

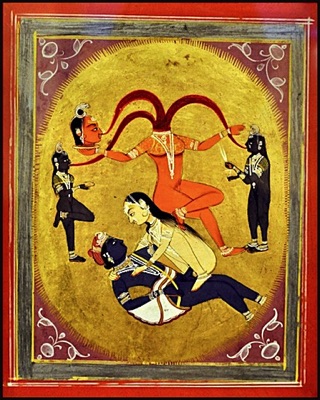

A few years before Samuel's arrival, Yoganarendra Malla, the king of Bhatgaon, died. In competition with the other kingdoms he had spent a lot of tax money on new temples.

In addition, he had devoted himself continuously for five years to the goddess Kamakala Kali – in order to practice 'the art of eroticism'.

When his own ministers poisoned him at the age of forty during one of his campaigns, the priests

and notables forced his thirty-three widows, whether or not drugged, onto the pyre.

Above all, however, the valley is a farming community. The soil is very fertile. Yet the population is poor, because only few own land.

Most of the farmland belongs to the kings, unless one of his ancestors gave it to temples or public works like water reservoirs. To pay the maintenance costs from the harvest yields.

The majority of the farming population has to earn extra income with spinning, weaving, pottery or other handiwork. Only the very eldest Samuel sometimes watches sitting in the sun in front of the shed or cottage, smoking a water pipe.

All other family members are working the fields, while the elderly keep an eye on the offspring playing outdoors.

As soon as dusk falls, they go to the small outbuildings or second floor at the nearest temple to sing ancient

texts, often accompanied by a moribund hand organ.

Samuel sometimes stands listening to the fragments of song through the dark, deserted village streets. There is not much variation in volume or pitch, each unison verse seems to have been written for a fresh, deep breath.

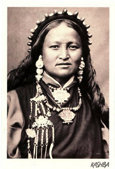

They consider themselves truly old, he has come to understand, when they remove the nuggets of gold from their ears.

The piggy bank from the years with good harvests must be passed on to family members in time, for if too late, it belongs to the burner of the corpse.

‘Yet, it seems they are celebrating a big festival every other week,’ Samuel marvels.

‘What do you expect,’ Giovanni laughs, ‘the harvest is in!

At the end of the rainy season, when the animals are at their fattest, lots of sacrifices are made at the countless temples and niches.

Nevertheless, Samuel turns away when the farmers let the blood gush from the neck of a buffalo, goat or

chicken over the hard stone statues – all those flies…

Under the condition that old traditions should not be disturbed, festival days remain sacred and free of any combat.

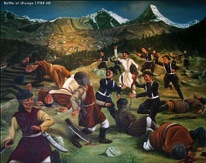

However, a standing army must always and immediately be able to attack. But the collection of young men is untrained, lacking proper management and good equipment.

No horses or elephants. No officers or captains. Merely infantry with knives, axes, swords and some old gun. Usually, a royal scion commands or else a minister may step in. Samuel even once sees soldiers dying during a fistfight between troops.

As padre Da Loro reports home: their wars last that unconscionably long because they actually are rather childish. The most important qualification for a soldier appears to be that he can run fast. Winner is the one managing to cut off an opponent's head anyway. Or if there are too many of them: their noses.

For themselves, the Newarese leaders pay for the protection by professional fighters from the traditional soldiers’ caste. But among themselves the elite virtually wage no war.

As for the farmers on the land, their life and work simply bypasses all skirmishes. Because of the war, they occasionally have to detour or cross the river a little further on.

Traditions and festivals – in honour of any god, momentum or seasonal change – keep together the valley called Nepal. All rulers are family belonging to the same high caste. You may also qualify their battles as military exercises.

Only together can they keep the valley separate from the outside world.

Families that fled from India have come to live in the middle mountains. Their soldiers are growing in number and getting closer.

So far they are too weak to attack, but their leaders use every chance to play the three kings off against one another (in which, not long after Samuel's departure, they do succeed).

Jealousy, rivalry and suspicion often render the royal policies capricious. Therefore, Samuel keeps quiet and wisely stays away from any court. The Capuchins told him what happened to Horace de Penna ten years earlier.

The padre had come from Lhasa because the young king of Kathmandu, Yagajjaya Malla, had granted permission to the Capuchin to restore their former, destroyed residence. At his arrival, however, Horace was imprisoned and sentenced to years of forced labour.

He managed, however, to learn Newari during the nightly hours and send off a small catechism to the king. Yagajjaya was not converted but the work convinced him that De Penna was not a spy. The capuchin was able to start the restoration of their centre after all.

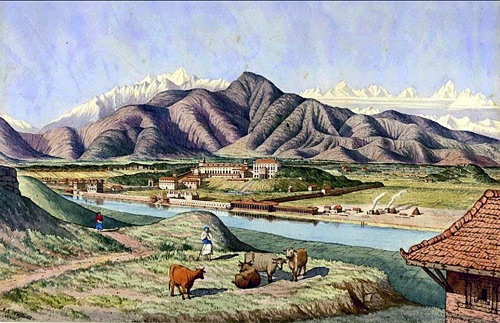

From the mountain peaks, Giovanni points out the trade routes that pass through the Nepal valley. From Tibet to India and vice versa. They provide the three rulers with toll and import duties and make the valley a well-stocked depot with many types of goods. Traders can not but stay for longer periods to adjust to the seasons.

Towards the lowlands they had better avoid the sweltering jungle full of insects and diseases during the monsoon from April to September.

That journey Samuel already has behind him, though he still is covered with scars of strange stingers and suckers.

Only in a few months, in March or April, will he be able to cross the Himalayas towards the plateau of Tibet.

The coming months the mountain passes are simply inaccessible.

Giovanni explains that the principality of Patan has a good route to India, but that all ongoing trade to Tibet must pass through Kathmandu. Too bad for Patan, because their trajectory therefore counts extra levies - even though this is somewhat compensated on the way back.

Bhatgoan is his own boss over all comings and goings which puts the principality economically on an equal footing with Kathmandu.

For trekking through the Himalayas, the capuchins refer Samuel to the bazaar, to the jumble of many narrow streets and inner courts around Asan Tole. To look there for traders who organise a caravan every other year.

He finds a group and at once notices that they are a different kind of Newari. Their bravado and airs distinguish them from the Newarese farmers who never leave their rice fields.

With Giovanni he sometimes met famers who had never visited the capital in all their lives, while looking out on it every day.

These traders travel back and forth every other year. Most of them keep families and households on both sides of the Himalayas. No different from their fathers and grandfathers.

It places them at the edge of the caste system, but they could not care less. Samuel is not only right on track with them, the traveller in him re-awakens as well. He asks to be allowed to join in the spring.

The burly traders, all born horse riders, see little difference between him and the pilgrims who join to walk a pilgrimage around the holy Mount Kailash. They are fine with him coming along; the more souls, the safer the journey usually.

The first part of the journey, however, goes straight up along narrow, steep mountain paths. All goods have to be brought in baskets to the high plateau by the merchants and carriers.

A few of them occasionally bind objects to yaks or goats, but they run the risk of falling behind and losing the protection of the caravan.

Older Nepali who need to go to Tibet but can not handle the height or the climbing, have local mountain dwellers carry them. They let themselves be tied onto a plank

and then usually blindfolded. Ten days to the border. From that point onwards reasonable paths run across the plateau and horses, yaks and donkeys are for rent.

In view of the cold on the plateau, however, you‘d better stay in motion and walk.

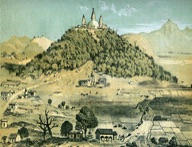

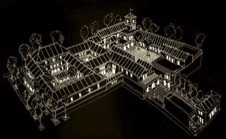

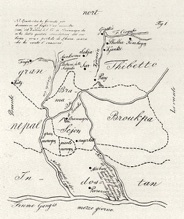

In the pale winter sun in front of the capuchin house the two proceed to map out the Nepal valley.

Samuel saved an old letter from Cochin and uses the reverse to make notes for the legend.

A month later they draw up a rough sketch of the areas around Nepal.

Meanwhile spring tickles his calves, the best season to go to Tibet has arrived and yes, Giovanni and Nepal have endeared themselves to him, but all those village goings on is are not for him… too long in one place makes him restless ... better roll up the mat and move on…

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty