Home

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty

Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

GESLOTEN / CLOSED

16 okt - 5 nov '25

Contact:

31-20 - 6 23 55 64

06 - 588 41 370

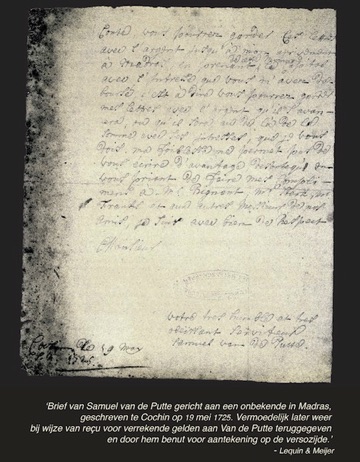

Cochin, 1724. Just like the sailing ships in the harbour, Samuel must refresh his supplies before departure.

For example, filling his purse. To cash a letter of credit, he has to visit the VOC office; because of the stiff commission it gladly acts as a bank.

In essence he exchanges paper money for silver money, which he changes again into strung copper coins whenever he needs to pay for his daily food, drink and stay.

He also tries to enrich his cherished medicine case by sweet talking one languid afternoon with the head surgeon. During the midday heat he likes to consult the maps at the company's office for the journey ahead. But, of course, lone wolves

like him are the ones that first map unknown territories.

There is one shortage he can only resolve by trying to get into the archives of the VOC-strongholds. For the mysterious land traveller, however, this usually takes little effort. After a few exciting or entertaining stories in the late afternoon, a pile of old documents only used one-sidedly are usually shifted his way.

After being constantly on the move for five years or so, the anticipation of hazardous situations or of getting sick has become his second nature. Samuel is alert, meticulous, picky and strict for himself. In loneliness similar to the famous Italian travel book writer, his forerunner Gemelli Careri, he makes notes about route, people and circumstances –without all the lamento at yet another desolato campfire though.

His journal, his loyal refuge, has become indispensable. It contains numerous names, addresses, routes, medicinal recipes, finds and findings. The notes have to last many more years, in all weathers. The durability of paper is of the utmost importance to him. After all his wanderings the sturdy VOC-paper from Zaandam is still his favourite.

In previous years, company ships took sheets of Chinese paper back to Amsterdam. These were made of soaked and beaten silk. Rembrandt forked out quite some money to be able to place a few of them on his etching press.

In Europe, people tried to mimic the process. In Holland, silk was replaced by worn-out rags.

That is to say: replaced by selected, washed, soaked and ultimately finely chopped linen.

Thanks to the presence of mills and water, the Zaan region in Holland manufactured a good, solid quality, albeit in small quantities. Since the arrival of book printing and increased commercial activity in Europe, the demand for paper could hardly be met.

Even a steady supply of rags from neighbouring countries could not remedy the shortage. A few decades before Samuel left home, an Amsterdam court even issued a decree that the dead were no longer to be buried in linen cloths.

France fabricated whiter and more elegant paper, but the mills around Zaandam produced a much more sustainable kind.

Its remarkable strength was not obtained by pounding the mash of soaked and bleached rags, as everywhere else, but by treating it with knives. According to order, sheets of paper were made suitable for goose feather, brush, printing press, or to pack some item.

For a long time, the highly polluting process was very profitable. The nearby farmers could hardly object to the stench and the filthy residual water, since it created plenty of jobs for their women. In addition to the knife-procedure, the Zaandam 'secret' consisted of many female hands sorting out the old, sometimes even germ-contaminated rags into at least seven grades.

In every region that he passes through, Samuel pays close attention to the materials on which the inhabitants keep their scratches and scribbles: stone, tree bark, hemp, bamboo, plant fiber...

Important texts are often noted on parchment. Animal skin, however, is equally costly and cumbersome everywhere. A simple prayer book may require a hundred and seventy calfskins or more.

Besides being stronger, the Zaandam paper from the local VOC archives is quite moisture-resistant as well - no insignificant detail for Samuel.

From Cochin on the west coast, he treks right across the interior to Negapatnam on the east coast. He finds a local boat that sails to West Bengal. He still hopes to travel along the Hugly River to Delhi in the north. To get to mountainous Uttarakhand, yet further north, to the old trade pass through the

Himalayas. From Portuguese brothers he learned that the Jesuits António de Andrade and Manuel Marques succeeded to access the Tibetan highlands by this route a century earlier.

But first, the sailing ship took days to carry him through the immense, totally inextricable Ganges estuary. No one but experienced, locally born captains can manage to find the entrance to the Hugli River.

The banks of the endless waterways are overgrown with mangroves, whence local, European or Asian pirates can easily launch an attack.

All the more when the ship gets stuck in the maze of shifting sandbanks.

Samuel, certainly no naval hero like his father, is holding his breath anyway since he found out that his boat is kept waterproof with oil and fish glue.

Individuals trekking beyond their own regions or countries in earlier times, usually were traders. Arabs, Armenians, Turks, Jews, Syrians, Indians, Chinese, Italians. Befriended families, though living thousands of miles apart, take

care of each other's stay. They are familiar with the other’s business interests, culture, habits, tricks, sorrow - as well as with their next generation.

This may sound more idyllic than intended. Because the other aspect binding traders for centuries has been the general defamation of their trade. It hurts that a merchant’s profit, apparently without much labour, comes at the expense of others.

On the subcontinent traders are regarded as a sort of lower caste of their own. The contempt sometimes is fueled and exploited by jealous princes and armies, as ever complaining about having insufficient resources.

By exchanging drafts and letters of credit – of which Samuel while traveling between the VOC offices is dependent at times – the trading families are bankers as well. Their alleged parasitic behaviour is a worldwide theme in books and theatre.

Yet traditionally it generally is the small trader who first crosses borders and breaks up the prevailing worldview at home of their country being the centre of the earth.

Their trade is an indispensable link between separate societies. Without any exchange between cultures, there is little economic dynamism and a community may get stuck in dogmatic power relations between a class living off its interest and an impoverished population.

‘The nobility keeps your poor and the church keeps you stupid.’ Samuel already heard the saying during his academic years in Leiden - and he noticed the pattern almost everywhere along the road.

With his talent for languages, Samuel likes to enter into conversations with merchants in trading houses and inns to exchange routes and advice. Above all, he likes to speak with roman missionaries, but he seldom meets them.

Conversely, things are different. None of them ever traversed such immense distances over land. Let alone for nothing other than satisfying his wanderlust. Even though he does so without causing any offense to anyone in particular, he is understood nor trusted. A pair of legs that show the world to a set of brains? How does that vagabond make his money!

Samuel is locally dressed and keeps a low profile. The fact that he does not speak the local language does not really surprise. Each region has several tribes and dialects, people are used to it. The only written language is the one of palace and temple - which usually is kept to confidants.

His biggest problem is paying daily for meals, shelter, clothing, toll or bribery. Not the paying itself, but the means of payment.

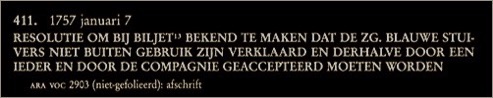

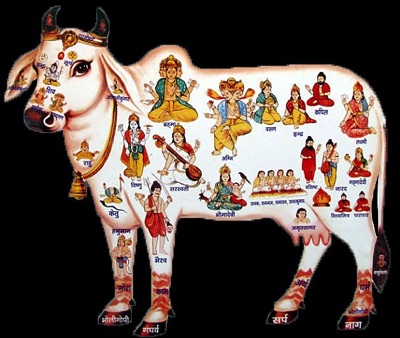

In India, the European companies mention three types of currencies: christian, mohammedan and pagan. In other words: European, Arab, Mughal coins. The money circulation, however, is endlessly diverse and complicated. Besides local rulers, foreign companies mint coins as well, for example English rupees. The acceptance and value of the coins vary with the extent of their power in the area concerned.

All coins need to be weighted and considered anyway. Among other things to determine whether or not – deliberately – too much precious metal has been worn off. In that case, more of it has to come to the table, a rather visual form of inflation.

In order to come to an agreement on the quality of the purchased merchandise as well as the value of the means of payment, also Samuel is sentenced to quite a few cups of sweet tea.

The older the coins, the less valuable and popular they are. Once the depreciation has become equal to the cost of minting, the old ones are recycled – which again yields a percentage for ruler or company and for users another load of marks, features and details to remember.

Like any trader or shopkeeper, Samuel carries a black stone with him to test precious metals.

For emergencies in isolated areas, Samuel sewed some silver and golden granules into the seams of his garments. His purse includes renowned international coins, such as the golden Arabian dinar and the golden Venetian ducat. On the Indian subcontinent he mainly gets by with silver reales and rupees.

Wherever necessary, he changes them into copper coins to pay for his daily living and sleeping accomodation.

Money changers explained to him how it is that, since Syria, he is increasingly handling silver Spanish reales. Strange, since pope and king do not allow the Spanish merchant to do any business with the islam world - because… Moors!

Consequently, Spanish merchants transport their huge quantities of Indian and Bengali textile via the Philippines to the New World, a giant market. Payment is made in reales or bars of South-American silver. With the help of genocidal slave labour, precious metals are robbed in Mexico and Peru.

In business terms: purchase zero, sales maximum, profit gigantesque.

In actual fact, textile prices – mainly consisting of wages – are inversely proportional to the local power of the company involved.

The name ‘real’ originates from the Roman language and daily reminds people that all precious metal actually belongs to the emperor. About the horrifying massacres to get gold and silver in South America for free, papal Rome and christian Spain remain silent in all languages.

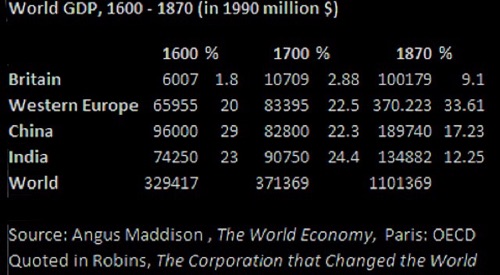

In Samuel’s days, the demand for silver in Asia has been almost insatiable for over a century. Both the Chinese and Indian populations are rapidly increasing – and as a result their economies as well. There is a chronic lack of payment means.

When brutal rebels founded the Ming dynasty in 1368, their first emperor tried to re-install paper money. Eventually by force. But the general distrust proved too tough. In private, larger debts were stealthily paid with silver as in the past.

Within half a century silver became the officially recognized means of payment. The rebels discovered that it was much easier to levy taxes on bullion than through, for example, servitudes or the collection of parts of harvests.

Unfortunately, in China - but in India as well - little precious metal could be mined. For some time domestic traders acquired some extra silver in Japan and Indonesia. It remained too little, however. The production and export of luxury items as silk and porcelain needed to drastically increase to obtain more silver.

In Chinese ports, the bars were tested by custom officers, hallmarked and declared legal currency. For daily use, some of the bars were melted into the well-known small ‘boats’ full of marks.

Some fifty years before Samuel's birth a world-wide market came into being. Since his birth, clever European trade

constructions earn exorbitant commissions as middlemen.

Especially from West to East: silver.

‘Our true gold in the Golden Age was silver,’ Dutch historians sometimes claim. To me, in the case of looting all turns gold – by definition.

Samuel's cradle stood at the origins of capitalism. In this political-economic system, the property one owns is actually considered as debt of the other, e.g. as a claim on his or her labour (in essence, one never purchases anything but the work of others).

Not hindered by academic nuance, it seems to me that not the plundered silver but the labour in the mines together with the underpaid labour in the textile factories eventually forged the continents together to a global economic whole.

For nearly a century the Spanish fleet has already been transporting the bulk of American silver directly to India and China for a long time. That is, via the Philippines to camouflage the loss of face of king and pope.

Even within Europe silver becomes scarce. The twenty percent of the Dutch population that has to pay taxes, regularly have their large showy dinner table art pieces melted.

Not so much because they can not pay up but because they lack other means of payment. The government uses their silver to carry out wars, but in the end the precious metal, like mercury, nevertheless flows towards the East.

Ever since Syria, Samuel has been traveling with silver in his pocket, coined by the Mughal in Delhi or by the Spaniards in Mexico. How the value of his last gold ducats from Venice relates to silver rupees, depends on where, with whom

and with what necessity he exchanged. As well as on the condition of the coin.

The VOC mints its own heavy silver dukatons, more or less equal to the half as heavy golden ducat. Within the company, its exchange value varies in the accounts of each branch office. It is the best evidence why VOC annual figures are never meant to be correct.

The East Indian Company, for example, agrees with a tax audit of the ledger every 21 years but finds it rather exaggerated. Whether the papers in question remain readable or even still exist in the tropics is irrelevant.

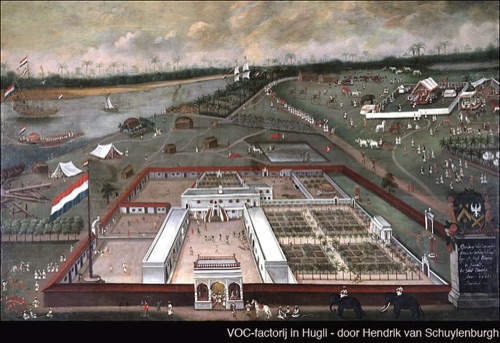

Having arrived in Chinesura, located upstream above Kolkata, Samuel observes how different the mentality of the local company is: even more suspicious and corrupt than in previous fortresses. The port mainly shifts huge amounts of textile, raw silk and wool.

It does not take long before he

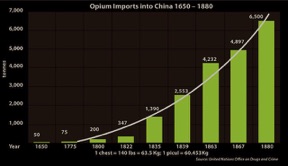

catches the fragrance of a completely different, less overt trade: amphioen.

That’s why the gloves are off here, Samuel understands.

‘What d’ye expect?’ a company servant shrugs his shoulders, ‘this here is the fattest pasture.’

Due to its high price, opium attracts a lot of smuggling trade.

Therefore, the VOC servants in Bengal set up a kind of sub-company among each other. Almost everyone within the fortress shares in this ‘tacit profit’. Those not wanting to participate are at risk - possibly for their lives. The one foolish high hat that proposed free market trade as a remedy for all smuggling, came off gently with a ticket for the next return boat. Lower ranks were killed. Native rulers were kept away from the black gold by regularly burning down a few of their villages.

In the absence of sufficient silver to purchase goods, each VOC ship is forced to a few years of intra-asian trade before being able to return with a shipload to the port of departure in the Netherlands – and its investors there.

An increasing number of ships settles the bill with opium – the black gold. While Samuel sails from Cochin to Bengal, 5,000 pounds of opium sail in the opposite direction to purchase 200,000 pounds of peppercorns. A pittance, according to the company ‘servants’, for it is not half of the pepper in previous years. To phrase it with an 18th century saying: the spill trade calls the smuggling trade black.

Behind closed doors the servants are working on a new strategy. Within a dozen years after Samuel’s stay, this will lead to the creation of the Society for Trade in Amfioen (a partnership of a few supreme VOC directors, government leaders and members of the royal House of Orange).

For the next one and a half century no chief merchant will board a return boat without having accumulated an unlikely fortune.

As a whole, the VOC has stopped making profit long ago.

Ever since Pieter van Dam's Descriptions of the East Indian Company 1639-1701 – though actually already since Linschoten's Itinerario from 1596 – it is known, in black and white, why one should stay away from amphioen. The Calvinist robber-merchants know all too well why dealing in opium is so incredibly lucrative, they see the outcome often enough around. Their justification is, of course, that opium is a great pain reliever. That users may become heavily addicted, well, that 'them heathens' must decide for themselves.

Since the VOC has its own army, the Society actually operates from Batavia as a narco-military kleptocracy.

By using, for example, small dealers to keep opium readily available around plantations, the workers in fact become serfs; rarely are they able to pay off their debts.

It makes the elite partnership of rulers and royals little more than a criminal pusher.

From 1500 onwards, South European ships have been transporting missionaries to the subcontinent as well: Franciscans, Dominicans, Benedictines, Capuchin and Jesuits. At strategic crossings, these Vatican storm troopers first set up private houses and later on, wherever possible, small monasteries.

Due to disputes and rivalry among themselves, for a long time territorial expansion often seemed more important than the actual conversion of natives. As the youthful jesuit Ippolito Desideri, having arrived in Ladakh around 1715, reported that he had discovered a very receptive meadow. By return brother mail, however, the order came to immediately break up and cross the Himalayas towards the Tibetan highlands.

When a group of English artillery soldiers passes by, on their way to Patna, Samuel is more than happy to go on board.

Not so much because of Tibet itself – the spiritual top of the world idyll had not been devised yet – but because it is closer to populous China. In addition, the Vatican imagines feeling the breath of protestant and calvinist missionaries in its neck.

Like Samuel, many Europeans are fascinated by the distant, magical-mystical empire where fabulous inventions and products originated from.

From the printing process to gunpowder, from porcelain to silk. To the Vatican the stringent confucianism seems to perfectly harmonize with their own doctrine. The ‘blind’ just need to be introduced to the right god, but after all, that's their mission. Extra ecclesiam nulla salus meaning outside the church no salvation.

At times the pioneering friars are so much impressed with buddhism that they cannot but conclude that Asia must have been christened before.

The triratna symbol (buddha, doctrine and effect) that they notice in the temples, for example, obviously corresponds with the trinitatis sign (the holy trinity). The possibility that much philosophy and religion originates on the Indian subcontinent is not recognized – 333,333 pagan images block their sight.

To the roman brothers, protestants still are heretics. Their community house in Patna receives Samuel favourably, though. His tawny, modest appearance does remind one of a monk by now.

He had learned that Desideri was passing through Patna and staying in the community house. He very much wishes to pay him a visit.

Forty-year-old Ippolito Desideri appears to embody the mantra of the jesuits: il modo soave, the gentle way. If you encounter resistance, change tactics by making compliant proposals or by ‘accommodating some of their traditions’ - as long as this does not affect our belief. In practice, this usually means embracing colourful trivialities, while sticking to your own agenda. The one pope is in favour, his successor is against. Sometimes, this or the other order considers the ‘accommodation’ too extreme, most of the times they mainly envy each other’s successes.

The double-hearted mentality of il modo soave runs through Desideri's blood, so much so that some brothers occasionally openly speculate whether he is a spy.

A Vatican fiscal, to remain in VOC terms.

But after so many years of experience with the arbitrary power of so many

different rulers, Samuel has become no less skilled in ‘soft tactics'. The two get along excellently - apparently at least.

Samuel is eager to know by what route Desideri recently returned from Tibet. He had to return because the mission centre in Goa had decreed that he had to resign his mission post on the plateau to the capuchins.

The Tibetan monastery which had offered Desideri shelter for a few years, was sorry to see him leave. They appreciated his ideas and the discussions he started – it takes one to know one. Open debate about doctrines is an integral part of their monastic education.

Desideri was a passionate intellectual. It probably doesn’t do him justice to say that he learned the Tibetan language and doctrines only to refute godless buddhism – but it did come down to that.

However, he was also interested in everything else: in the life of the population, their habits and history, the nature on the roof of the world.

The commitment of the shrewd jesuit sharply contrasted with the approach of the other brother orders in Lhasa. Essentially, their approach was to keep the door open and wait for a request for help - and then casually strike with conversion.

When Samuel meets him in Patna in November 1725, Desideri has already completed his ragguaglio (report to Rome). The questions put forward by the inquisitive visitor, however, help him sort out what will eventually become his 800 pages of Notizie Istoriche del Thibet (which impressive work, first of its kind, is immediately locked away in the Vatican catacombs for centuries).

On every map in Europe, the Tibetan plateau, Samuel’s foreland, is still a large blank. Ippolito, however, is brimming with information. Samuel takes plenty of notes.

‘More than twenty completed sheets,’ one of the brothers later grumbles in a letter.

Desideri tells him to forget about the route through Ladakh. Due to the collapse of the Mughal dynasty, the long trek is too unsafe.

Besides, the Himalayan pass is only briefly open, at the most for some four months. Why not go through Kuti, the mountain pass at Kodari, the way back he himself took. He can write a letter of recommendation to the brothers in the Nepal Valley who’ve set up a house there.

Towards the end of 1726, after the rainy season, Samuel joins a group of Nepalese traders with hundreds of carriers and mountain donkeys. The procession strings through the principality of Bihar where crops have long since been harvested.

At the end of the barren, dusty plain, the Himalayas extend over their full width.

'Shiva's resting body,’ a Madhesi farmer points out with a broad gesture.

As he walks, Samuel looks fascinated at the series of white mountain tops floating in blueish haze above the horizon. Down below, the promontory abruptly starts, resting on a remarkably straight line of bearing.

The scurrying traders are eager to hike the pace. They want to return in time to the Nepal valley with their saris and rolls of fabrics. For the Dashain festival will start soon, when parents have new clothes made for their children and themselves.

In short, the kind of festive days they themselves rather spend at home.

Main sources:

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty