Home

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty

Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

GESLOTEN / CLOSED

16 okt - 5 nov '25

Contact:

31-20 - 6 23 55 64

06 - 588 41 370

On the particularization of stones

in

INDIA – NEPAL – TIBET – CHINA – JAPAN

–– INDIA - NEPAL ––

Was it out of poverty that small villages – across the Indian plains or up a Himalayan mountain range – installed a stone from the surrounding nature in their temple and not a detailed effigy?

Actually a simple stone is the most elemental symbol of human impermanence. All chiselled texts and ornaments hitchhike for a while towards eternity but weather long before the tomb-, memorial- or prayer stone itself crumbles into stardust.

Even in ancient temples of larger cities you may find similar time-washed stones in the heart of the sanctuary. These buildings are usually situated a bit forsaken and neglected along a river – where the farming community, small and impecunious, once emerged.

Often the stones are of a simple beauty, with or without a layer of oil and chicken shit. They provide us with a glimpse into the ancient perception of the forces of nature – long before a shaman, sadhu, baba, priest or other mediator between heaven and earth had made himself indispensable for the interpretation of a many-armed effigy.

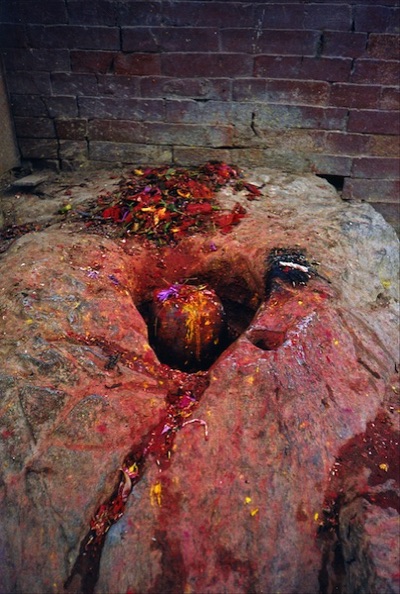

Mother is identified with stones in which a thousand years of streaming water eroded a hole or slot: the yoni.

Father is represented by the elongated phallic shape that a rolling boulder sometimes acquires in a brook or river: the lingam.

As for a son, a paunchy rock is much loved.

Still, the question remains why mankind does not view a stone – or an image - for what it is, but attributes all kinds of names and powers to it and subsequently projects his heart and soul onto it.

‘To set at least some beacons in that elusive infinity of the universe! As an attempt to some positioning in this eternal All and Nothing, who knows!’ my Sunday morning jogging friend reacted to my musing and picked up her pace.

Thus she inadvertently summarized the use of stones in Tibet rather nicely.

–– TIBET ––

Marking one’s bond with a spot by placing a stone when departing, is a worldwide tradition. The custom to leave a memorial or pilgrim stone behind in a holy place, on a tomb or along a path, is as old the road to Rome.

On the icy plateaus where paths regularly disappear under snow, Tibetan nomads and travellers pile up loose stones to form beacons – hoping these will continue to stand out in the dazzlingly white world.

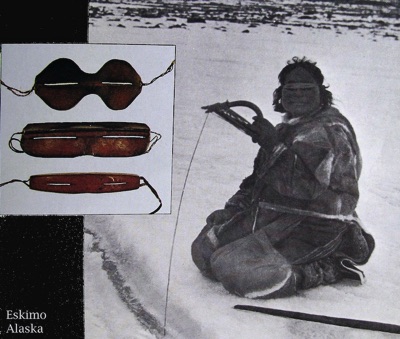

Tibetan snowglasses made of smoky topaz.

Snowglasses made of leather, wood or bone, Alaska.

A stack of five stones refers to the five essential buddhist doctrines and is thus both literally and figuratively a signpost.

Whoever stumbles upon such a heap of stones in that silent timeless limbo, unwittingly pictures his predecessor who upon arrival at the same spot – with the last sunrays withering away and chilly shadows closing in from all sides – was clowning with five boulders to indicate the right direction for the next likewise benumbed fellow traveller; compassion as a compass on a godforsaken icy plateau.

The grizzled area between tree- and snowline mainly consists of gravel and boulders.

Therefore, one better over distinguishes such a stack of guide stones. Tibetans like to add a chiselled mantra or effigy.

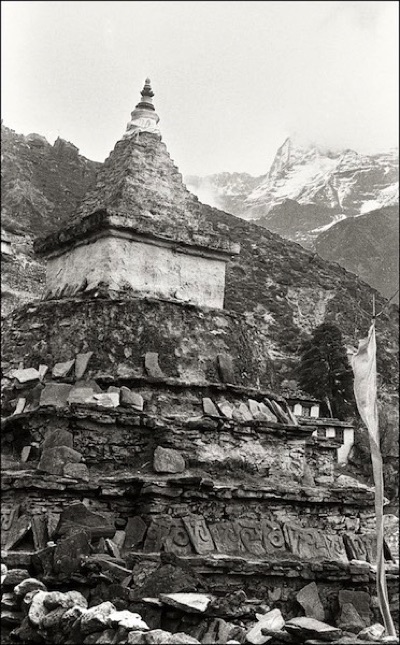

Invariably an elongated pile of pilgrim stones leads a trekker in and out a mountain village.

Also around the main temple, gompha or chörten sits a variety of carved stones, generally bearing the mantra of wisdom and compassion:Om mani padme hum

- Om mani padme hum

Attempts to interpret this best known mantra often gets stuck in a long explanation of the two key words: mani (diamond) and padme (lotus). The popular translation as 'the jewel in the lotus' is rather nonsensical and meaningless.

The attention focusing om and the closing sound hum need no explanation here. They enclose and distinguish the two essential key words, which refer to the two most important scriptures in Tibetan Buddhism: mani refers to the diamond sutra and padme to the lotus sutra.

Very briefly described: the first teaching is about knowledge, the second about compassion.

Very simply imagined: knowledge in itself can result in something like the neutron bomb, compassion in itself gets stuck in pity.

Only knowledge and compassion combined lead to insight, wisdom - love.

Endless

repetition of the mantra is meant to make this understanding one's own, to 'intertwine with one's own being'.

Without design, scripture or symbol a stone in the surrounding ‘All and Nothing’ would apparently remain meaningless to man

In China, however, they thought differently.

–– CHINA ––

The higher the expectation, the greater the disillusion – sure, but nevertheless that’s what it came down to once again. Early in the morning we had entered Beijing’s Forbidden City.

We wandered from courtyard to courtyard, ever consulting booklets to get an idea for whom all those hundreds of rooms hidden in courtyards were meant: craftsmen, counsellors, eunuchs, concubines...

The fact that nowhere, truely nowhere, one could look over the surrounding walls, gave us – long before noon – the oppressive, claustrophobic feeling that the imperial clique must have lived in for generations.

In the late afternoon we finally made it to the imperial gardens. Where we expected splendour of sculptures and decorations, the ancient trees mainly housed big jagged boulders.

We saw no diagonal lines flowing through complex patterns, no deep vistas, tight undulating ridges and sloping folds – we only saw uncuddlable skin-hostile rocks on pedestals.

Just as incomprehensible as the elucidation that in ancient times these tons of stoneweight were painfully and carefully dragged – on wooden carts with wooden wheels – from the deep south to the imperial city.

In all likelihood this love of remarkable, large stones or gongshis – gong spirit shi stone – started a few millennia earlier in temple gardens. However, some thousand years ago, scholars - those who could read and write – began to collect much smaller specimens.

Reading stones grew into an art form. Such a scholar's rock could be meant as a meditational focuspoint inside the tray, but could also serve as a brush-founder, ink stone or incense burner.

This depended on whether the stone was considered abstract as a mountain, cloud – or representative as mythological animals or Shinto spirits.

Four general stipulations were applied through the centuries. The rock should not have been formed by human hands. The type of stone had to be hard, yet rich in texture. Hue and luster were to give the stone an honest, classic look. And finally, the appearance was not to be flat but suggestive.

However they were used, all were embraced and appreciated for their aesthetic merits. The abstract, yet formal qualities of Gongshi that appealed to scholars of the past are the exact same qualities that appeal to collectors of today.

Ancient Chinese believed Gongshi contained the basic life force and like people, underwent profound changes in the course of their development. Modern aficionados see earth as the ultimate artist. Yet, past or present, the appreciation of Gongshi has always been rooted in the aesthetics of form tempered by imagination.

And this appreciation, often manifesting itself as reverence, gave rise to another interpretation of the word Gongshi: ‘Fantastic Rocks’. – suiseki.com

'It is always the instantaneous reaction to oneself that produces a photograph.’ - Robert Frank

After drawings of Chinese temple gardens were seen in Japan around the year 600, petrofilia took roots in that country as well, where it was subsequently refined into Suiseki – a intriging and costless form of art accessible to anyone with heart and eye for nature.

–– JAPAN ––

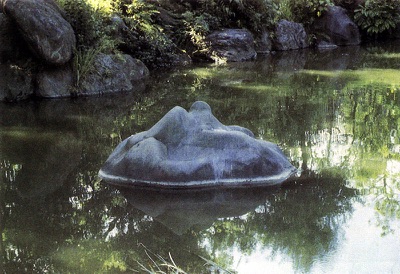

For Japanese buddhists, this stone symbolizes Mount Shumi, the mythical centre of the world.

For taoists, this formation of stones symbolizes Horai, the Taoist paradise.

It is believed that the emperor Go-Daigo (1288-1339), after losing a political battle, fled from his palace to Mount Yoshino taking with him nothing but the above pictured suiseki.

With amazement similar to that of today’s westerner, a fifteenth century Japanese peasant or warlord must have gazed at the 'dry gardens' constructed by Zen-monks in the hills around Kyoto. 'Wet gardens' they were familiar with, since these crossed the ocean centuries earlier from China together with Chen buddhism.

The Italian garden aims to express an intellectual and philosophical vision of nature; the English garden is mainly based on the idealized world of the pastoral idyll; but the Japanese garden uses nature in a highly symbolic way.

With its carefully thought out gravel patterns around a few significant rocks, the dry garden is worldwide known as Zen garden.

According to legend the initial idea was to suggest a dry riverbed.

In the fifteenth century monks changed the image into an ocean with islands - with corresponding symbolism.

An ocean in Mahayana Buddhism stands for what nowadays may be referred to as universal consciousness.

The indigenous religion of Japan, Shinto, regarded the islands as dwellings of ancestral spirits – in buddhist terms: the karma of descent.

These small islands were buttressed ‘under water’ by the backs of turtles to indicate their timelessness.

Tibetan images sometimes show how these two interpretations can fuse into yet another form, as on this panel with symbols and animal heads emerging from amidst the waves of the ubiquitous ocean.

Neither shintoism nor buddhism keeps the Japanese collector from developing a personal relationship with his stones, which is sometimes called anthropomorphic projection.

Anthropomorphism, or personification, is attribution of human form or other characteristics to anything other than a human being. Examples include depicting deities with human form, creating fictional non-human animal characters with human physical traits, and ascribing human emotions or motives to forces of nature, such as hurricanes or tropical cyclones.

Anthropomorphism has ancient roots as a literary device in storytelling, and also in art. Most cultures have traditional fables with anthropomorphised animals, who can stand or talk as if human, as characters.

– Wikipedia.

Phallic stones. More pictures here.

According to Yuji Yoshimura Suiseki collectors – the current readers of stones – speak amongst eachother in century-old terms such as:

See: On displaying a collection

Wabi – melancholic, lonely, unassuming, solitary, desolate, calm… the classic image being an abandoned fisherman’s shack on a lonely beach on a gray wintry day.

Sabi – ancient, serene, subdued, mellowed, mature… the distinguished appearance of a treasured antique.

Shibui – quiet, composed, elegant, reserved, refined… the understated elegance of a formal tea ceremony.

Yugen – obscure, dark, mysterious, profound, uncertain… the early morning mist veiling a mountainside.

The four keywords overlap too much for some collectors. They prefer to describe their beloved stone with a poem. For example with the ancient, anonymous:

A bird calls out

The mountain stillness deepens

An axe rings out

Mountain stillness grows

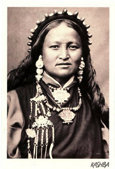

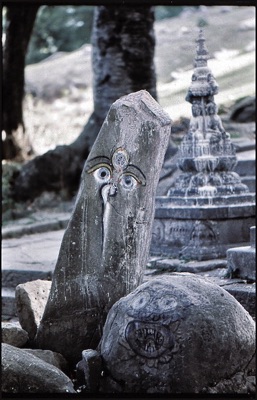

Swayambhu nath, 1973, Nepal.

Apparently, the touch by man makes a stone sacred – just as a person comes alive through his or her significance for other human beings.

‘So be it,’ the abstract art creating artist sighed. Slightly irritated he looked away from the spontaneously expressed associations of the spectators. ’The work does sell better if people think they recognize something in it.’

Not very different from the motto of the flea market merchant: ‘It always appeals to someone.’

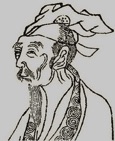

'Each man has his own preferences:

All things seek their own companions.

I have come to fear that the world of youth

Has no room for one with long white hair.

I turn my head and ask this pair of stones:

‘Can you be companions for an old man?’

Although the stones cannot speak,

They agree that we shall be friends.'

– Bai Juyi (772 – 846)

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty

'In the oldest religion everything was alive, not supernaturally but alive.

There were only deeper and deeper streams of life, vibrations of life and more vast.

So rocks were alive, but a mountain had a deeper, vaster life than a rock, and it was much harder for a man to bring his spirit or energy into contact with the life of the mountain, as from a great standing well of life, than it was to come into contact with the rock. And he had to put forth a great religious effort.

For the whole life effort of man was to get his life into contact with the elemental life of the cosmos, mountain-life, cloud-life, thunder-life, air-life, earth-life, sun-life.

To come into immediate felt contact, and so to derive energy, power, and a dark sort of joy.

This effort into sheer naked contact without an intermediary or mediator, is the root meaning of religion.

- D.H. Lawrence

'It is always the instantaneous reaction to oneself that produces a photograph.’

- Robert Frank photographer.