Home

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

Contact:

31-20- 6 23 55 64

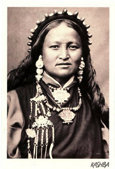

Kalu Kumale (1933)

Father was a small farmer. Like his neighbours, he made earthenware pots in the alley in front of the house during the quieter seasons. Once in a while, he - or whoever was on call in the neighbourhood - would take a fully loaded handcart through one of the surrounding villages or towns.

As a teenager, apart from pots, Kalu sometimes made animal figures as well - a useless fancy of a youngster. At the age of twenty-two, sudden illnesses confined him to bed for a longer period of time.

In order to support his young family, he kneaded animal figures and tiny toys in bed. A friend had them cast in brass and tried to sell them for him.

Once he was back on his feet, he visited a few foundries and sculpture carvers more frequently. Poor as he was - and perhaps worse in those days, coming from a different, lower caste - he tried to copy the craft.

A few years later, a sculptor, Sangh Ratna Shakya, asked him to help with the workload he suddenly received.

In those days - the fifties and sixties - many monks and other refugees fled Tibet and crossed the Himalayas. With them they regularly dragged antique sacred images along that had been smashed by the Communist Red Guard.

Many of Tibet's ancient monasteries were simply blown up with dynamite.

For Marx and Mao considered religion to be ‘the opium of the people’, it obstructed the 'cultural revolution’.

Many of the images, however, had been damaged during the weeks-long flight: a broken arm, lost symbols and so on.

For about two decades, Sangh and Kalu restored these damaged statues. The sculptures varied in quality as well as style. Kalu was especially fascinated by the savage, angry figures. Gradually he learned to sculpt wax models in that specific, tantric style.

His interaction with the fugitive monks also influenced him. He adopted their stern, austere lifestyle. For the rest of his life, he got up at three in the morning for meditation and a morning walk. After food he worked from noon till eight in the evening.

His lifelong, stern work ethic meant that his work found its way into many

Together, the images above form the eight manifestations of Guru Rinpoche or Padmasambhava. We bought the set in the eighties. Only recently we found the right, matching thangka, as well as the space to display the set properly.

The statues were made according to the lost wax method, then chiselled and fire-gilded.

Their height varies between 25 and 35 cm.

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty

There were hardly any schools in the valley - but there was no money for that anyway. Still, this generation had it slightly better than the previous ones.

Before Nepal opened its borders in 1951 and the Rana dictatorship came to an end, grandpa was often forced to do all kinds of unpaid work for higher castes.

With no schooling or experience, it was not surprising that his first sculptures appeared somewhat stiff and sparse. But in time, Tibetan monks recognised the quality of

his work.

In 1970 he was commissioned to make a gift for the fourteenth Dalai Lama: a statue of the Palden Lhamo, the only female protector of the doctrine. Seated on a horse and as tall as 108 cm, the statue made a big impression.

In the years that followed, he received assignments from various monasteries in Nepal, Tibet and India.

In between, he, the devout Buddhist, replaced

ancient public sculptures for local communities whenever thieves had looted them at night. This Dhanwantari statue, for instance.

places in Asia, Europe and the United States.

Mostly installed in monasteries and temples, but also, for example, on display in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

In the latter days of his life, Kalu Kumala was showered with awards in his own country.

After Nepal opened its borders in 1951, he certainly did his share in making the traditional, high-quality Newarese arts known worldwide .

Some insiders even wonder whether the ‘calm creator of wrathful gods’ – as The Himalayan Times (1-22-’06) named him – has not been a great stylistic impulse for Newarese art in the recent decades with his own specific tantric style.

‘Now I am 71 years old and still intend to continue my profession as a sculptor,' he said in a 2003 interview. ‘This art is our nation's heritage and I am proud of it.’

Mostly loaded with various sizes of water pots. For even if a house had a modern water pipe, it would only provide water for about an hour a day.

Like all children in the neighbourhood, Kalu used to play with the clay that father prepared for use. As the umpteenth generation of their jyapu caste, the children were after all destined for a similar existence.