Home

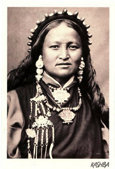

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

Contact:

31-20- 6 23 55 64

Guanyin is a centuries-old representation of the human being who is caring about the world.

She or he portrays full attention. Selfless, ego-free attention. Only then is there space for compassion, love.

He or she represents the awareness that you live thanks to the others in this world.

Even the Mao-regime considered Guanyin apart from religion ('opium for the people').

S nr. 3 - 36 cm

Boeddha. S nr. 15 - 43 cm

Lin. nr. 2 - 37 cm

L. nr. 7 - 35 cm

Loaded to the brim with fragile porcelain, innumerable Chinese boats for centuries drifted down the streams: from the upper Dehua Valley to the Fujian Delta.

From there larger junks shipped it to other coastal towns

From the 16th century onwards, there also were European merchant ships waiting for trade, farther upstream they were not allowed.

No idea how many weeks it took such a small boat. Our long-distance taxi flies over viaducts and tunnels itself for

miles right through inconvenient mountains - and in the end takes three hours.

The old inner city seems to be replaced by new buildings from the outside.

(If in past decades the profit of World Factory China was invested in anything, it is foremost in its own infrastructure. Whether new roads run along abysses in the Himalayas or through tunnels in mountainous landscapes, they seem indestructible.

On the Indian and Nepalese side of the Himalayas, parts of the road surface are washed away every rainy season - and their construction worlds don't mind at all. Chinese roads, however, have a sensible drainage system underneath the road at vulnerable points - and that is something the dictatorial system deems rather obvious.)

Baskets full of porcelain.

According to collector Robert H. Blumenfield - author of Blanc de Chine on white porcelain from the Dehua valley - there was 'an intense chinamania’ in the first half of the seventeenth century. (In the English language the word china still refers to porcelain).

S. nr. 12 - 30 cm high.

‘Millions of pieces of Chinese porcelain, including Blanc de Chine, were imported by ship to Holland and other European destinations.’

A number of monarchs, aristocrats and wealthy merchants in Europe were maniacal collectors of the range of graceful shapes, made of that exotic, fascinating material.

Even in Calvinist Holland, less than a century after the iconoclasm, Guanyin statues were appreciated for their refined elegance.

Still, I have not come across her so far on any antique painting. That may be my fault, but perhaps it is also due to the grey shadows needed for outlining a white surface - like teeth; they have a tendency to be out of tune in a colourful 17th century still life.

In the 18th century Porcelmania is also about the struggle to reconstruct porcelain in Germany (Meissen) and England (Wedgewood).

Many of the current characterizations still originate from French, which at the time was popular in elitist circles: celadon, famille verte, blanc de chine, sang-de-boeuf.

Since Marco Polo - true or not - returned with the first porcelain bottle to Italy, the unknown, white material is named after the 'pig shell' porcella, now known globally as kauri shell.

Through the centuries virtually all blanc de chine came from Dehua. There it was bought or ordered by traders, government officials or Taoist scholars.

A small percentage of the Guanyin images found its way to more distant Asian countries, in particular to Chinese emigrants in port cities such as Singapore, Manila and Batavia.

The fact that Buddhist symbolism traditionally dominates the images, may be because Japan also formed a large market – until the prolonged import ban came into force in the mid-17th century.

(Although Shinto is the prevailing popular belief in Japan, it virtually offers no hope for a possible life after death (reincarnation). Because of this, Japanese elderly turn to the Buddhist monasteries – which consequently receive many legacies.)

The fact that Dehua porcelain remained relatively unknown in the west throughout the centuries, was mainly because since the year one thousand all imperial porcelain came from the only other region with good porcelain earth, Jingdezhen, which is also closer to Beijing.

As a royal supplier, the region enjoyed imperial protection, which meant that delivery and quality could generally be more constant.

The Dehua Valley is still rather unknown.

Even ceramist/writer Edmund de Waal does not mention the blanc de chine from Dehua in his 2015 book on porcelain - which, it should be noted, is called 'The white road' and has the opening quote from Melville's Moby-Dick on an empty, white page:

What is this thing of whiteness?

Since the nineties we had been buying countless variations of blanc de chine regularly from a quiet, knowledgeable trader in Beijing. Until the good man suddenly disappeared from the face of the earth. Perhaps he wanted to leave, far away from his wife whom we amongst ourselves named Mrs Mao, after the shrilly screaming member of the Gang of Four.

So seven years ago we decided to find the way to Dehua ourselves. Via the famous port of Xiamen - not knowing that via Quanzhou is more direct.

However, most sculptors proved to live too far from the city and too dispersed in the surrounding hills; in the vicinity of the ovens, near the veins with the right kind of porcelain soil.

We returned home empty-handed – but it kept nagging. So last November we decided to try again.

(Just before we left, auction house De Zwaan gavelled off the greater part of the interior of an Amsterdam canal house.

Among the numerous '19th and 18th century blancs de chine' we noticed four that were coming from us; apparently they were deeply shocked and instantly aged after crossing the threshold - indeed, it is a hard world out there.

All the more reason to have another try in Dehua.)

Hotelwindow

The valley village of yesteryear turns out to have been developed into a real city. Surprisingly fast and drastically. Wikipedia mentions 300,000 but in our opinion it now counts some million inhabitants - perhaps still a village, as far as China is concerned.

In the centre of Dehua.

The city has no taxis. It has a kind of uber system that we cannot digitally call and pay. However, many people are willing to take one to the studio of a friend or family member.

At the end of a purchase, smartphones are facing each other with QR-squares mutually blinking: the commission flies right by your nose across the table.

No problem. How else would we have found the studio in a city that is expanding so fast that now and then neither the inhabitants nor their route planner can figure it out.

(Not so long ago, bank payments - a condition to be able to export - took about five to ten working days. Here, from a laptop in the hotel, it sometimes turns out to have been transferred within 24 hours.

‘Capital that is pumped around the world like mercury' has become a very ancient, mechanical description.)

Since a few years the city boasts a couple of streets with new, chic porcelain galleries. Remarkably, the older antique shops look neglected or closed.

Could the realization that real, good antique porcelain has since long been stuck in collections and museums have finally sunk in?

Not to mention the fact that porcelain without solid provenance (origin) is practically impossible to date with any certainty.

Imitation ?

‘This could not be more complex in a country where copying is a valued pathway of respect, a way of learning skills. The repetitions of a previous reign’s achievements is noble in itself.

And anyway, I add under my breath, I’ve been trying to make these kinds of pots for decades. That crackle glaze has never come right for me. I would have given anything to have been able to create a bowl like that one, let alone repeat it.’ (De Waal)

B. 10 - 65 cm

Clearly the galleries are doing good business here. They promote the work of old and young artists.

Their signed Guanyin images usually cost three, four, five thousand euros.

B. 5 - 45 cm

The gallery owners, often themselves ceramists, are surprised by our interest in Guanyin. Westerners rarely drop by, let alone for Guanyin.

At the breakfast table in the hotel we noticed some businessmen but they were clearly in large-scale, industrial projects.

HOPE and HAPPY also turned out misbaked.

The domestic market of one and a half billion is more than sufficient for Dehua. In part the new, signed sculptures are bought with the hope of the artist's increasing name recognition - and corresponding price increases.

If we indicate that there will be little enthusiasm at home for these precious creations, however beautiful and special, they sometimes turn out to have a completely different price without a signature.

Every image - of whatever price - has been worked on by many professionals. From mould-makers and assemblers to stokers and glaziers.

As with any artist who works with lost-wax technique, the signature is mainly about the design and sometimes a little bit about the finishing touch.

Not unlike painting studios, even when it says Rembrandt or Dali at the bottom.

Traders, however, want a name as a brand so that an internationally valid monetary value can be linked to it. No different than an x-computer with x-power, a diamond with x-gradation clarity or a piece of original Scottish shortbread.

Such a pity, because more co-workers usually means more expertise. Each does what he or she is good at. For example, workshops sometimes engage an external steady hand to set up all lines in one smooth movement.

‘One piece of porcelain goes through as many as seventy hands, the work may not be interrupted’. Père d’Entrecolles (1664-1741).

’For this reason, the men round the borders of the pieces and the blue bands are entrusted to the workers who sketch the outlines, learn how to design, not how to paint in colours, while those who fill in the colours are taught colouring, not designing, by which means the hand becomes skillful in one art work and the mind is not distracted.’ (T’ao Shuo – scripture)

‘And by making one man do the grasses, only grasses, the numbers of mistakes drop. You can also identify where things are going wrong and who to punish.’ (De Waal)

'In China, where eras of taste are measured in centuries, the tradition of innovation took place over centuries and not in individual years.' -Blumenfield

In other words: changes in taste and design do not take place in years but in centuries. Yet blanc de chine invariably depends on its white.

The process of making porcelain requires a remarkable amount of energy from man and material, but when the carefully selected kaolin and the long-purified porcelain earth finally fuse above 1400 degrees Celsius, that brilliant white can come into being - a white that people for centuries could not describe otherwise than: like porkshell, like goose fat, like eggshell, like white jade...

Especially after the porcelain has also absorbed a glaze layer, endless discussions have arisen for centuries about the exact whiteness of an object.

‘Does this white have a thick pink or thin pink tint?’

- Pink? There is some green in it!

‘And this then... goose white?’

- With all that yellow in it? No, ivory white!

‘Why are you holding it to the light?’

- How else do you want judge the underlying shrimp tones..?

Dehua owes its characteristic white to the extremely low iron oxide (think of rust) content of less than 0.5% in the local porcelain earth. To some extent its density does contribute as well.

While compassion may never have

been depicted as specifically masculine or feminine throughout the centuries, in the workshops it is striking that the Guanyin statues take shape through women's hands.

A tender touch apparently is indispensable when assembling arms, head, and other parts – within the short time the clay actually lends itself to it.

A loving approach seems just as desirable when applying symbols and decorations such as shaping some bits of clay, ball by ball, into a pearl necklace around the neckline.

Even the shipment of the many statues came about thanks to women (and translation programmes).

Prices vary from € 55,= (15 cm) to 495,= (90 cm).

Average size (40 cm) and price: € 145 / 195,=

Many of the sculptures come in their own, handmade, upholstered box.

More samples see here

Arrival Staalstraat Amsterdam

A vase symbolises water of life in which life germinates.

The lotus rises through dark water to sunlight: enlightenment.

From ‘Blanc de Chine’ - Blumenfeld

More about porcelain:

Jingdezhen, porcelain city for a thousand years

Porcelmania (history)

Chinese porcelain etc in shop

10 jan. 2019 10:08

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty