Home

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

Contact:

31-20- 6 23 55 64

‘Why don’t they brew beer or something?’ a hardworking friend quips when it comes to monks. She has little sympathy for ‘those beggars with their chaste monastic life.’

She dedicates herself, nevertheless, on a daily basis to people who cannot participate in our capitalist society, where not participating is no longer an option since the proverbial cabin in the woods has also become priceless.

And yes, she does respect the diligent workers signing up for a ten-day retreat at a monastery in the province of Limburg at the rate of one hundred euros per day. Nevertheless, to her a monastic life remains synonymous with a parasitic life.

In Burma such criticism would fall flat – but for how much longer…?

‘We do not beg!’ I overhear a novice defend himself in clear English at similar allegations by a German tourist. ‘We ásk nothing.’

Early in the morning they take to the streets. Often for a short procession, rather thinly clad and barefoot – even in the cold mountain villages. Their performance is a rehearsed discipline:

walk straight, be silent, look straight ahead, and keep the pace.

Until someone halts them to donate some food. Without so much as looking at the person, the row briefly holds their steps. Not a word is exchanged. Each monk in the row opens the begging bowl, the giver donates.

Mostly white rice.

Of course the silent procession slows down if they see from the corner of their eyes an elderly man or woman rushing forwards to catch up on them.

Of course, the young novices at the back of the line cannot hold their tongues all the time.

And of course in the evening a few monks can be spotted in some out of the way small teahouse, nibbling at something while watching a Kung Fu movie.

The eldest monk - literally - leads the way, clutching his empty bowl against his chest, he doesn’t carry anything.

At the back the youngest novice drags the Tiffin carriers in which the group receives vegetables or dahl soup. This takes time, so the kid regularly falls behind.

Again and again he must make haste and run, because the procession keeps its pace without looking back.

Past noon, monks are no longer allowed to eat anything, that’s why.

Officially at least.

Once daylight manages to pierce through the fog over the mountain village, I hear a novice beating a flat bell outside indicating that a group of monks is approaching.

Boldly I join them and try to make some contact on the way. In vain. Stoically they stick to the rules and pretend they do not notice me.

That is more difficult for the smallest kid at the back. Again and again we spurt together to catch up: he with his Tiffin carriers and me with my camera. Soon enough we stealthily joke a little, literally behind the group’s back.

When I hold still after half an hour and stare at the disappearing line, some of them - stiffly – nevertheless turn their heads to see whatever happened to that foreign buffoon.

Curiosity still beats discipline.

‘It is the monk’s duty to give his fellow man the opportunity to develop generosity,’ the young monk explains to the German woman. She does not take the hint, but she nods approvingly, she finds the theory beautiful as well.

Before I realize it, I am standing in front of a classroom full of monks.

Perhaps some traumata still lurk from the past, when it was the other way around at the Christian Brother’s school, I feel at once very much in the wrong place.

The monks look at me quietly and expectantly. When people do not have a common language, they sometimes assume that their thoughts are not understood either. But faces at times speak volumes, and I do not read a favourable opinion of westerners. Quite understandably, the British colonials acted here more bestially than in the surrounding countries.

But the hands of the foremost monk mesmerize me and I venture to capture them.

The atmosphere turns shriller.

Until suddenly it dawns on me - ‘we ask nothing’ - that I apply the wrong order. Clumsy and embarrassed I put tea money for fifty men on the table.

The ice breaks -– somewhat.

From their side monks are not allowed to refuse a gift.

Recently the government of Sri Lanka asked the populace to provide the monks with better food.

Research had shown that there was a higher than national-average rate of diabetics among them.

The monk can never be blamed.

I once enjoyed asking a pompeus Tibetan lama whether his intense focus on the spiritual was not at the expense of the physical.

Prolonged lotus-sitting can not be very beneficial to the temple of the soul. Yoga as well as tantra originally include both meditation and body exercise.

My question was not appreciated, even though next to the pig (ignorance) and the snake (disunity) also the peacock (vanity) is shown in the centre of the Wheel of Life as one of the main three poisons in the world.

Burma is so far unfamiliar with these problems, nearly everybody is skinny, but how long will it take when you watch the modern busy-busy buddhist choose the easy way by offering monks finished products such as packets of instant noodles, cake, chips or candy bars...

A monk can hardly sniff at the offered food first or scrutinize the wrap.

It is his duty to accept, to help others to develop goodness and consequently to a better karma.

Some of them I noticed giving the bad food to dogs, but how buddhist can that be… and who knows what your own reincarnation will be …

‘Giving is easier than receiving,’ well-off westerners sometimes psychologize. Buddhism regards the two actions as more equivalent.

Probably Sri Lanka and Burma are among the last countries where the buddhist monastery - sangha in Sanskrit - still preserves much of the original design. These are also countries where monastic and social life are still strongly intertwined.

These are also countries where monastic and social life are still strongly intertwined.

More than two thousand years ago the first buddhist followers roamed the Indian plains.

They were wanderers like their Hindu brethren, the sadhus and babas, who also abandoned their social existence – and still roam the plains to this very day by the hundreds of thousands.

The twelve-yearly Kumbh Mela festival, when about eighty million people make a pilgrimage, dates from that beginning.

After his death, the first followers of Sakyamuni went – sometimes in small groups – to annual meetings and places of pilgrimage as well.

During the monsoon, when the trails got muddy and impassable, they lingered for some time in one place, for example in a cave or under a group of large trees.

Sick and elderly brethren needed a safe stay for a longer duration. The first permanent shelters, known as viharas originated in a landscape that remained virtually unchanged for thousands of years.

In the sixth and seventh centuries northern India in particular had large numbers of monasteries annex universities, also for non-religious studies such as medicine, astronomy, and so on.

They were open institutes, spiritual orders that one could easily enter into or leave. They were communities that in the eleventh and twelfth centuries had little defense against the belligerent attacks – and prosecutions – from areas like present-day Mongolia, Iran and Afghanistan.

The number of several hundreds of monasteries – a remarkable number in view of the world population of less than 500 million at the time – dropped to virtually zero. Buddhism fled to other, more easterly situated countries as Burma and Thailand or across the Himalayas to Nepal, Tibet and China.

The spiritual and secular powers in these countries may seem to be opposites, but they can hardly do without one another.

Monasteries often practice martial arts and armies like to call themselves Protector of Buddhist State.

A former soldier may very well enter a monastery at an old age.

Even today, anyone can quite easily enter into of leave the sangha – a matter of picking up the bowl or placing it at the trunk of a tree.

Because of their striking attire the image in the international media is primarily of monks standing up against the junta – think of the Saffron Revolution of 2007 or of the numerous

resistance comes from all walks of life, not only from the layer of singles that walks or hides in monk’s clothing.

Students, farmers and the labour force actually risk more. Not only do they

The monasteries – some 50,000 in number – currently lodge four to five hundred thousand residents. An equally large number of Burmese leads a military life.

Sangha and army mirror each other in recruiting and training young people – but the spiritual and the secular lives far from complement each other. Both get their influx preferably from poor, remote villages.

A city dweller unintentionally gave an example of how a sangha gets its necessary finances: ‘I’d rather donate for young monks than paying up for their boozing parents in those backwater villages. They’ll die at an early age anyway.’

And with a small smile: ‘Hopefully donations will be of some help for my karma in the next life.’

For a long time the iron distinction was: in the monastery you learn more, in the military you earn more. With the establishment of administrative and training systems the British occupiers tried to reduce and take over the role of the sangha as well.

If the Junta ìs the State, revenues constitute no problem for the military. In recent decades it consequently won more and more ground upon the sangha. A soldier has access to better shops and hospitals and indirectly his relatives profit as well – you can leave all types of bribing to the junta.

Presently, about a third of the population is – directly or indirectly – economically dependent on the military system.

‘In dealing with oppressive regimes, we need to try to understand them. That is why books such as this are important.

But while reading about dictators responsible for the suffering of millions of people, we should not focus just on their personal characteristics and their actions. It is even more important to keep in mind the circumstances, the reasons why all of this happened and why they could do what they did.’

Foreword in 'Than Shwe' door Václav Havel.

For decades people have been referring to the junta, both in conversations and in print simply as they - everybody knows who one has in mind.

'Whether or not they formulated their actions as crimes against humanity – they did not know the concept – they felt this should not happen. (…) They said: we would never do such terrible inhumane things. They said: "We are Buddhists, how could we do such things to our own people?!”

They understood it was unacceptable.’

Yozo Yokata, UN Special Rapporteur 1991-96.

As effective as the demonstrations in the streets of Rangoon were the times when the joined sanghas flatly refused any gift from the military - unheard of in buddhist Burma.

‘On two occasions monks turned over their begging bowls and refused to accept offerings of food from the military. The junta considered these incidents as treacherous acts of defiance, no less.

'The images of these brutal actions against the most revered figures in the society (the monks) were seen on international television and, even more important, by many Burmese through satellite television.

The population was horrified, and it became evident that however much the junta had tried to build up its image of religiosity (because of personal beliefs or for political legitimacy purpose or both), they had lost the authority they so assiduously cultivated.'

Burma / Myanmar – David I. Steinberg

'It wasn’t until 5 September 2007, when monks – long a behind the scene player in politics – denounced the price hikes in a demonstration in Pokakhu, that the protests escalated. The military responded with gunfire and allegedly beat one monk to death. In response, the All Burma Monks Alliance (AMBA) was formed, denouncing the ruling government as an ‘evil military dictatorship’ and refusing to receive alms from military officials, a move that stunned the government. ‘If generals were going to visit their monastery, the monks would disappear,’ one local in Mandalay told us a couple of months afterward.

- Lonely Planet

Things were different at the time of the independence war against the British dictatorship. Spiritual liberation through the buddhist path was considered of a higher order than the worldly liberation the revolutionaries pursued.

In many colonies the emergence of the independence movements took place during the tail end of a tenuous global cultural understanding which a certain, worldwide intellectual elite cherished at the end of the nineteenth century and which in an even fainter degree somewhat united them; from Calcutta to Casablanca, from St. Petersburg to Paris – and Rangoon.

Nehru en Gandhi

They were educated, had knowledge of the history of the planet and what humanity had so far accomplished, such as the ancient civilizations the world had known. In Asia, there was a class of scholars that knew all too well

From such backgrounds came freedom fighters like Nehru, Gandhi, Hatta, Sukarno, just like Aung San in Burma (left).

They were schooled by their occupants, often with a university degree in the home country of the oppressor.

During WWII they sided with the Japanese to bring about independence in their own countries – or rather: back to the pre-colonial situation.

During the war Japan turned out to be anything but a liberator – a role that would have made the Rising Sun of independence in their own countries –

For centuries the Burmese have been known as a pugnacious albeit literate people - retaining power requires knowledge.

Still one may come across books with unexpected titles spread out for sale along the sidewalk.

Books, booklets and leaflets, well-thumbed and yet hardly damaged.

For a couple of days we rented a car with a driver who first, early in the morning, before we could leave the village, had to pass by the local branch of the National

After Aye Myint had thoroughly quizzed me about which authors I had read and what I thought about them, he decided to show me his book collection. It is not easy to get English-language books in Burma, but his collection numbers over a thousand volumes, the result of decades spent scouring secondhand bookshops. As he puts it, he ‘retired from the world’ in his early twenties and for the past forty years has lived a hermit-like existence in Mandalay, sequestered with his library and one spinster sister in a two-story wooden house that they inherited from their parents. The interior of the house was dark and cool. The front room was crammed

Finding George Orwell in Burma

- Emma Larkin

U Ottana and Aung San – the ever popular father of Aung San Suu Kyi, murdered in 1947 – were supporters of Mahatma Gandhi's nonviolent resistance but founders of the current army in Burma as well.

Like all other young people they had spent some time during their childhood in the buddhist monastery, the sangha. And just like Nehru and Sukarno they had a university education in England.

Once in power, they tried to reduce the power of the monastic communities with slogans such as ‘You can only give to the sangha if you first take care of yourself’ – not very different from the British occupiers.

The country needed to be included in the rise of the nations – a development to which particularly the army formed an obstacle.

It's a bit strange to travel a country where decades of violations of human rights take place while each street view shows numerous monks.

Although the junta at times still fires rockets into isolated areas on minorities like in Kachin, one hardly notices the absolute dictatorship in the cities.

Except for the caution and suspicion of the people as you try to get past the weather chat.

Compared with visits in the eighties and nineties a significant turnaround is taking place: people are eager to tell you stuff, but at the last instance nevertheless prefer not to.

Since last year (2012) dictator Than Shwe remains in the background. The new head of state, Thein Sein, seems more moderate but functioned for years as his right hand.

As many a dictator Twan Shwe liked to busy himself with major infrastructural expansions: bridges, roads, a completely new capital including a giant pagoda,

The first revolutionaries who fought for the liberation from the British - in close collaboration with freedom fighters in India - wanted to proclaim Burma a Buddhist state.

A decade later they still considered themselves buddhist, but - saluting the new rulers in neighbouring China - rather called themselves a socialist government.

Also red, but with less shades than saffron.

When, in the nineties, dictator Than Shwe was tackled by an American diplomat about the ruthless suppression of student riots, he replied without batting an eyelid:

‘We’re buddhists, we don’t even kill a fly.’

A monastery in Burma is rather a social than a spiritual institution. It includes a home and school for children – whether orphaned or not – from poor families. As a result you see few begging homeless children in the streets –– quite in contrast to neighbouring countries.

At the same time the sangha is also a home for singles. Older monks – who you involuntarily associate with a long life of contemplation – sometimes turn out, when you speak to them, to have been living there only for a year.

Some members of the workforce say they plan to join once the children will have left the house or as soon as they no longer have any social duties or functions.

This is consistent with the millennia-old thought: the first part of life consists of learning, the second part of creating (family, work, society) and the third part provides time for contemplation.

Donors I asked about it, estimated that one-third of an average order is concerned with spiritual development, at the utmost. By that they generally meant assisting the population in times of illness, old age and death.

This ‘volunteer work' could also be described as the practice of the bodhisattva thought: compassion.

The percentage of monks that actually focuses on the spiritual path to enlightenment, is minimal.

Almost all doors and windows are open when I walk along the accomodation. The wooden houses are empty and pleasantly draughty. The teak floors have a fatty shine, you can tell the generations of bare feet that passed.

On crisscross stretched ropes red wraps hang to dry or air. Thin mattresses lie rolled up against the walls. Here a few talkers, there an occasional sleeper, a pile of books, a stray begging bowl…

The sight touches something that I obviously still carry along in my ever more hectic, capitalist western consciousness: the wish to cut loose and let go all at once…

Within religious orders women usually have a subordinate position as well. Reportedly Sakyamuni, the historical buddha, initially preferred not to have any females among his followers.

Of course, two thousand years ago it hardly suited their wandering lifestyle. But even today no saddhu or monk hangs around with a woman (exceptions as the Tantric Nyingmapa school aside).

The monastic rule that was introduced only later still exists and often reflects the position of women in buddhist cultures. Even the oldest nun remains formally 'junior' – meaning subordinated – to the novice. And so a woman can never achieve nirvana if she does not first incarnate as a man.

Meanwhile, leaders like the Dalai Lama have commented on the situation– at the insistence of other (western) cultures.

That the exclusion-rule has existed for millennia, is even more peculiar when you consider the many female deities in the Buddhist iconography that embody essential doctrines.

‘Is it true that according to Buddha women cannot reach Enlightenment?’ the student asked.

Without looking at her, the master replied, "Yes, that is correct.’

‘Really!?!’ She looked at him in bewilderment.

‘Do not think as a man, do not think as a woman,’ the master mumbled as if it were a mantra, ‘think nothing.’

"But I am a woman!’ she protested strongly.

The master looked at her and said: ‘Very well, be a woman.’

Yet it is remarkable that this one monastic rule does persist in Burma.

‘Burmese women had equal inheritance rights with their male siblings and retained control over their dowries. (…) Early English observers felt that the status of women was higher than that in Europe at the time, and one British observer in the early nineteenth century believed that Burmese women were more literate than English women.’

- David I. Steinberg.

Coming from a culture where women for centuries – under social coercion – had been stepping into the cremation flames of their deceased husbands, Mahatma Gandhi repeatedly expressed in his speeches in Burma (1922) his amazement at and admiration for the independence of the Burmese woman.

Presently, the number of women at university surpasses the number of men, according to Steinberg.

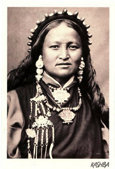

Female monks in Burma, more than 40,000 in number, do not wear saffron-red but countless shades of pink with orange accents. As traditionally red pistil threads were set aside for men, why not opt for the yellow stamens of the same crocus flower?

Perhaps because yellow and orange already refer to other buddhist schools in surrounding cultures.

However, it has been some time since vegetable dyes, which in bright sunlight all faded into the same indistinctive tint, were exchanged for harsh, colourfast fabric paints.

It strikes me that the male monks get boiled rice donated into their bowls and the female monks uncooked. Are the men not allowed, unwilling or unable to cook for themselves? No doubt a profound reason will have been constructed over the ages, but no one could enlighten me.

After making their round, the women's group that I followed one morning sold the excess rice back to a female rice trader.

‘Yes, yes, there is Theravada ánd Mahayana buddhism,’ the two novices agree, elbowing each other aside in their enthusiasm to have their English heard.

‘And we are Theravada, the old school.’

- But there are more, I tease them. Isn’t there Tantrayana as well?

‘Oh ... yes,’ they smile furtively. 'But we have no such experience, sir... ‘

- I thought the Theravada school didn’t have so many statues, I change the subject, but I see many buddhas here.

They consult with each other - this is a serious question - and after one minute come with a joint reaction:

‘If you love your family, you are happy to have their pictures, are you not?’

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty

So, before our era, hundreds of monasteries came into being on the present Indian subcontinent.

protests against the junta’s heavily polluting, exploitative factories.

lack the protection of a robe, they put their families in danger as well.

Every foreign camera lens, however, reacts like a bull to the photogenic saffron – mine included.

the propagated European superiority to be nothing but suppression tactics. Apart from all the remarkable inventions. Or better yet, because of them, as a result of which the West for centuries had the better weaponry. As stated, the European managed to organize the lie excellently.

Nevertheless, in addition to the Asian scriptures this elite of scholars had the Penguin series of classics standing on the shelf as well - and read. As its western counterpart was familiar with Vedic and Buddhist scriptures in that rarefied world culture between 1850 and 1950.

Wealth wasn’t per se involved. This socially active stratum ranged from school teachers in small villages (Indian pandits are a good example) to Russian or English professional military or doctors on quiet foreign fronts, Egyptian diplomats, writers in South America, and so on.

Rarely does one read about this global, erudite stratum, which should or even could have prevented world wars – and which rapidly died out after 1945.

or rather: back to the pre-colonial situation.

During the war Japan turned out to be anything but a liberator – a role that would have made the Rising Sun of Asia forever popular in Asia – but tried to return as a colonial power.

On January 4, 1948 British Burma stopped to exist. Initially the new republic was called Burma - after its original people, the Burmese. In 1989, the junta changed the name into Myanmar – in order to annex the twenty percent non-Burmani.

Library to return the book he borrowed in the previous village and read last night.

While waiting in his postwar Japanese diesel Toyota, parked in front of a kind of USSR building at village level, the thing that intrigued me was the title of his loan book. Too bad we had no common language to find out.

with sagging wooden furniture. An empty teacup sat on the arm of an old planter’s chair, and the glass-fronted book cabinets were filled with old newspapers, their corners orange and crackling with age. Two grandfather clocks stood in opposite corners of the room, each telling a different time.

Aye Myint led me upstairs to where his books were kept. A thick carpet of dust lay across the wooden floor, and a narrow trail of footprints marked a pathway from the staircase to the bookshelf to a reading chair and back to the staircase again – a map of Aye Myint’s entire world. His books were stored in trunks, and he opened one for me. Each book was carefully wrapped in a plastic bag to protect it from the white ants and mould that destroy so many manuscripts in the humid, tropical climate of Burma. He started pulling out volumes.

‘Hans Christian Andersen!’ he shouted as he tossed me a beautifully illustrated collection of children’s stories. ‘O. Henry. Somerset Maugham. James Herbert.’ A well-thumbed edition of ‘Rats’ came flying towards me. Aye Myint reached deeper inside his trunk. ‘Earnest Hemingway!’ he bellowed as he pulled out a copy of ‘For whom the bell tolls’ folded up inside a used coffee-powder bag. ‘Ah-ha, Hemingway!’ he said. ‘Now, do you know why he committed suicide?’

I was saved from having to answer when Aye Myint stuck his head deep inside his trunk and emerged with a triumphant cry: ‘Ha! George Orwell!’ He uncovered an old Penguin copy of Animal Farm. It had the familiar orange and white stripes on the cover, and yellowed pages that felt very slightly damp. He told me it was the first novel he had read in English. ‘It is a very brilliant book. And it is a very Burmese book. Do you know why?’ he asked, poking a finger enthusiastically in my general direction. ‘Because it is about pigs and dogs ruling the country!’

I had already told Aye Myint that I was interested in George Orwell, and he soon unearthed a worm-eaten copy of Nineteen Eighty-Four from the growing piles of books on the floor. ‘Another very brilliant book,’ he said. ‘It is a particularly wonderful book because it is without the –isms. It is not about socialism or communism or authoritarianism. It is about power and the abuse of power. Plain and simple.’

He said that Nineteen Eighty-Four is banned in Burma because it can be read as a criticism of how the country is being run - and the ruling generals do not like criticism. As a result, he told me, I would be unlikely to meet many people in Burma who had actually read the novel. ‘Why do they need to read it?’ he said. ‘They are already living inside Nineteen Eighty-Four in their daily lives.’

‘This modernistic interpretation came to project the buddhist quest for deliverance from universal suffering into a quest for social deliverance from political and economic evils. '

Myanmar Nationalist Movement (1906-1948) in India - Rajeshkhar

etcetera. His projects were counselled by priests and astrologers but defined by military power conservation and according to insider sources achieved by forced labour.

I nod and let it rest. Would they indeed have any relatives in their native villages cherishing a picture of them…