Home

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty

Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

GESLOTEN / CLOSED

16 okt - 5 nov '25

Contact:

31-20 - 6 23 55 64

06 - 588 41 370

Once you learn about the blend of kaolin and petunse, you will never again handle a porcelain statue, plate or cup indifferently.

Indeed, the Maladie de Porcelaine or Porzellankrankheit, known from time immemorial, may strike: Porcelmania.

Already as a kid you’d better not let me do the dishes, and also later, as a merchant, I kept at safe distance from that cold, slightly posh if not fussy material.

Only after visiting Jingdezhen and Dehua, did it dawn on me. On a large area outside the town we strolled from quiet studio to noisy workshop, from quiet drying chambers with long, slender shelves to large blazing kilns where racks with assembled modelling work were rolled into.

Gradually I realised that the very fragility of porcelain gives it such dignity and charm. Vulnerable as the reflection of sky-blue with clouds in a flat-lying mirror, charming as a high-heeled pencil skirt.

Kneaded, casted and modelled, after each phase the clay objects get a different, precisely determined place within the calculated heat of the kiln. In order to gradually build up an imperishable strength - which may be broken again with a single tick.

At first Marco Polo did not care much for porcelain either. The simple, small gray-green-white jar he brought back from China to Italy in 1291 did, however, fascinate many others in Europe. What exactly did that wondrous material consist of, that Venetians soon associated with the smooth, white skin of porcellani, literally tiny pigs, a smooth sort of sea snails.

At the time quite a few European princes and merchants invested in alchemists who claimed to be able to produce gold – and with the changes of the market –maintained that that white gold was within their scope as well.

To proclaim yourself an alchemist in medieval times, you had to be an inspired fool. After all, you traded

August, August, described as the splendour-loving elector of Saxony, later king of Poland, was one of those lifegreedy men who took such baits. Once the student pharmacist Johann Böttger said out loud that he could make gold, he took him into his palace.

Within a year, Böttger thought it wiser to flee. He was caught and imprisoned in fortress Königstein. After all, the creative fool had in fact managed to bake a heavy kind of reddish ‘porcelain’.

To prevent his knowledge from being lost, August asked Von Tschirnhaus young but already an expert in magnifying glasses and firing techniques – to assist the foolish Böttger. Von Tschirnhaus had studied in Leiden and even visited the potters in Delft.

The two were lucky to find the necessary kaolin close to Meissen. On January 15th, 1709, they presented August, king by now, with eight white reinterpretations of Chinese examples.

‘This meant that Böttger regained heavy surveillance: ‘ninety soldiers, twenty petty officers and a drummer.’

By now spies swarmed Dresden and Meissen to learn the exact composition of the kaolin and the technique of glazing.

Böttger died at the rather young age of 37. Besides tuberculosis and epilepsy,

Too bad for the porzellankranke August, who, thanks to a collection of - in the end - 35,000 pieces of Chinese and Japanese porcelain, always had the bottom of the treasury in sight. Nevertheless, his new palace was inaugurated with a grand dinner whereat everything was served in Chinese porcelain - unprecedented in 1716.

Only after the seventeenth century Jesuit Père Francois Xavier d'Entrecolles had been stationed in Jingdezhen and explicated in two historical letters how china was made in China, did Europe begin to realize that porcelain consists of two raw materials.

It is from kaolin that porcelain draws its strength, just like tendons in the body. Thus it is that a soft earth gives strength to petunse which is the harder tock. A rich merchant told me that several years ago some Europeans purchased some petunse, which they took back to their own country in order to make some porcelain, but not having any kaolin, their efforts failed… Upon which the Chinese merchant told me, laughing: ‘They wanted to have a body without bones to support its flesh.’

This story gave Edmund de Waal the starting point for his new book, The White Road, journey into an obsession:

'You have to understand the dual nature of this composition necessary to create a smooth, plastic clay body that can withstand the firing in the kiln.’

Experiment is the only way, according to him. Despite all expertise, the final outcome remains unpredictable and subject recurring unforeseen factors.

The latter proved to be of vital importance through the centuries. For the potters themselves the work was mostly sheer poverty, with for instance pneumoconiosis as a result.

Because the firing process failed twice, three times in succession, several workshops in Delft went bankrupt to the cost of the amount of wood needed each time to reach the high temperature of 1250 degrees Celsius or 2280 Fahrenheit (which only an experienced potter could somewhat 'measure' by the colour of the flames).

The margins for the Jingdezhen producers were even smaller and extremely unreasonable, to put it politely, compared to the percentage that the mandarin and the merchant made.

'Père d’Entrecolles:

I hated it. Over fifteen, eighteen, twenty hours, I’d try and nurse the kiln towards a heat that would make my glazes melt, the colour of the clay change from grey. Firings scared me. The intensity of the fire, the knowledge of just how badly I’d built the kiln, the sound of the kiln straining, the need for this firing to work to make up for the last months, the malevolent lick of flame over my gloves as I pulled out test rings. I knew

Père d’Entrecollesc: saw people ‘so poor that their bones are buried in pits, rather than in tombs. He sees clay-makers who can’t leave their compounding to come to church unless they can find someone to take their place. (…) He writes a letter about how things are made, but it is actually about compassion.

The Amphritrite, the ship that brought him to China, loads up to start the long journey back to France. It takes nine months and it arrives at Port Louis with letters from the Jesuit missions and bales of silk and lacquer and 167 crates of porcelain from Jingdezhen. This is advertised in the Mercure galant, the gossipy What’s On for the

Export was essential for the not particularly fertile region which moreover attracted many workers from the interior. A pleasant side effect was that exports were paid in foreign silver coins that did not need to be re-melted.

'Evidently the Chinese normally transacted business with bar silver, which was frequently adulterated with base metals and had to be re-refined to verify the silver content.’ - Père d’Entrecolles

In The White Road De Waal visits places that played an important role in the rich, sometimes even exciting evolutional history of porcelain, such as Venice, Versailles, Dresden, Plymouth, Cornwall - it 's really quite simple, a pilgrimage of sorts.

But obviously he starts in Jingdezhen.

Say tulips or yak butter and people spontaneously fill in Holland or Tibet. Say Jingdezhen and there is silence. Yet for more than a thousand years much of the world's porcelain has been coming from this village – nowadays a big city.

For The White Way De Waal preferably delves into local archives in order to sift through the adventurous explorations of those few, zealous madmen and geniuses who were frantically searching for the process and the proper raw materials.

But to record their experiments, their cheating, their failed relationships as well – in short, the mountains of financial, social, emotional and porcelain shards their dreams and workshops left behind.

De Waal’s perseverance is known from The Hare with the amber eyes. He's a kind of ferret who works his way through a dozen volumes of an art magazine to add a detail to the final book.

In the second half of The White Road, the European part, he mainly describes the pioneers who tried to turn porcelain making into an industrial process:

Colbert (Versailles), Von Tschirnhaus and Böttger (Meissen, Dresden), Cookworthy and Wedgwood (Plymouth) – and numerous others who, with a tenacity bordering on mania, plunged into the adventure with all their tangible and intangible possessions.

De Waal consistently calls himself a potter, and that is evident from his book as well. From the marriage of kaolin and petunse, it seems, mainly pots and jars come forth and occasionally somewhere an extramarital small bowl or jug. He doesn’t like all porcelain and illustrates very nicely why:

'If you look at the cases of eighteenth-century porcelain in any museum, a shelf of palely loitering Vincennes, two of Sèvres, a bit of Bow, they seem irredeemably precious. Not only you can not work out what most of this stuff was for – a trembleuse, a chocolatier, a girandole – but there is a mismatch between

I have a bowl, eight-sided, lobed and pinched, ten inches across and four high, with a sort of raised basketwork pattern, and a flat gilded rim. It is from Meissen, around the 1780s and it sits primly on a high foot, as if expecting to be the centre of a table and hence the centre of attention. There are panels on the outside with pears, apples, plums and cherries, and on the inside is a bouquet of fruit, redcurrant and strawberries and gooseberries and half a pear.

It is valuable. Its insipidity is total.

I’m not sure if its horridness is that everything is

What is this thing of whiteness? the opening quote from Moby Dick reads on the first and otherwise empty page.

'A white object reflects all light that reaches it. (...) Like most colours people see, white is a mixture of all colors from the visible portion of the spectrum. Some consider pure white light as a light that has no hue. ( ... ) White may be called a ‘summation colour” because white is made up of all the colours of the spectrum.

This only applies to light; when, for instance, one would mix paint of all the colours of the visible spectrum, the result will be anything but white. -Wikipedia.

Buddhist novices in Tibetan monasteries have been learning to debate these kinds of issues for centuries. About light, from and to which all colour originates and returns and that, according to the relevant texts, is golden like the sun.

(Proposition: ‘Red is a colour but gold isn’t.’ Counter reply: ‘If gold is not a colour, then what is it?’ Or something similar. With each statement they clap their hands - or start a fight).

While his friends played outside, Edmund preferred to play with clay at a neighbouring potter. In each chapter you feel this love never extinguished.

‘This can happen because porcelain is so plastic. Pinch a walnut-sized piece between thumb and forefingers until it is as thin as paper, until the whorls of your fingers emerge. Keep pinching. It feels endless. You feel it will get thinner and thinner until it is as thin as gold leaf and lifts into the air. And it feels clean. Your hands feel cleaner after you have used it. It feels white. By which I mean it is full of anticipation, of possibility. It is a material that records every movement of thinking, every change of thought.

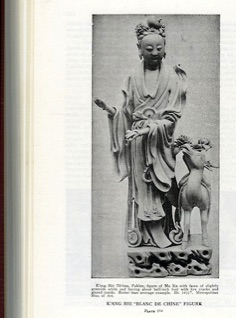

It is rather strange that De Waal visits nor names the region of Dehua, nowadays a city, renowned in China for white porcelain. From white sculptures (Guan Yin, Lao Tse) to white round goods (dishes, pots, plates, cups) and white pressed ware (water drips, brush holders, etcetera). Dehua, however, never gained the patronage from the emperor nor now from De Waal either.

Warren E. Cox (1956): '

The pure white wares were not popular and are seldom seen because there is a growing itch to decorate if not with design at least with rich colour Then too white was the colour of mourning and such wares were demanded by the court and probably also by lesser households for such ceremonies. (…) The finest clay was put aside for them for by now they had to be flawless to sustain appeal. The finest are called t’o t’ai or bodiless waferthin ware and Père d’Entrecolles tells that some had to be put on cotton wool for fear of damage and the glaze had to be blown on it as it was not safe to hold and dip.’

De Waal doesn’t even use the 19th century names Blanc de Chine or Dehua ware. Maybe to save his own work from the association with mourning.

Or perhaps to stay away from that other form of porcelmania with antique dealers and at auctions.

Like the macho bidding in 1986 at Christie’s, for instance. On old crockery from De Geldermalsen, sunk in 1752 in the South China Sea. High prices were offered in 1986, the total cargo fetched fifteen million euro euros. Nowadays you may find the same pieces on the internet for half price, at the most.

R. H. Blumenfeld: The De Geldermalsen was a typical Dutch East India ship, returning from China to Europe when it was lost off the Indonesian coast.

Interestingly, 95 percent of the value of the lost cargo consisted of tea (according to the original shipping documents, preserved in Holland). The ship also contained more than two-hundred thousand pieces of porcelain and even a small quantity - about a hundred pounds - of gold. The porcelain was ordinary and did not contain any great pieces.

‘I just went to have a look at the open day in the Cornelis Schuyt,’ an elderly friend told me at the time. ‘Quite a strange sensation. All those cups, saucers and plates that for three hundred years have been perfectly preserved on the bottom of the sea. Oxygen couldn’t touch it. No, I 'm not going to bid, it looks like it was bought at Marks & Spencer’s yesterday. Apart from a whiff of green, perhaps.’

Inspection day At Christie’s auction in Amsterdam for the porcelain called Nanking Cargo from the VOC-ship De Geldermalsen. 19 April 1986.

Père d’Entrecolles: ‘After what I have reported, one should not be surprised to find that porcelain is so expensive in Europe.’

Deplorable is that at all times new porcelain is undervalued as old porcelain is - inversely proportionally - overvalued. As indifferently as people often handle new porcelain, so fearfully old pieces are left in the cabinet.

Sour for toiling porcelain makers but they may find some satisfaction in knowing that nobody can ever be certain whether a piece of porcelain is truly an antique - let alone with pseudo-like precision as: from 1607.

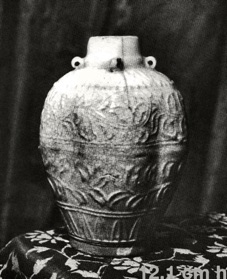

‘This image is early Ming period.’

- How can I tell?

‘By the style.’

- But ... how do I know it actually dates from that period?

‘By the old stamps, the patina, the provenance.’

- And never they used the style and seals again?

Perhaps because they liked it. Or just because a plate or cup was broken?

‘No, sir, they did not.’

De well known collector Robert H. Blumenfield in the book Blanc de Chine, the great porcelain of Dhua:

‘Indeed, for many years the appellation ‘Ming’ was ascribed to virtually any kind of Chinese porcelain in order to provide a sense of rarity and distinction. (….) Many modern pieces even have been stamped with marks of the Ming dynasty. Pieces with master He Chaozong’s mark might have been produced any time in the last four hundred years.

Joseph McDermott, professor Chinese history:

’A Chinese home, whether urban or rural, has retained (through its 4,000-year history) the basic farmhouse structure with walled enclosures. A piece of eighteenth-century porcelain may be shaped just like three millennia earlier. A twentieth-century calligrapher will often write in that earliest style of Chinese writing found on oracle bones nearly 4,000 years ago.‘

- Robert H. Blumenfield: Westerners today view originality as a sign of artistic greatness. The Chinese, on the other hand, view hommage to past masters as a fitting symbol of humility. Chinese artists therefore will deliberately cast their work in the style of design tradition of the greatest in their fields.

Drogen in de buitenlucht

Wall of workshop, Jindezhen

- R. H. Blumenfeld: ’The connaisseur may better keep to these three characteristics: condition, rarity and beauty.'

Voilà.

Across the narrow, wet streets of Jingdezhen we heard a soft strange sound echoing in the early hours. Only after we unexpectedly stepped into a workshop, did we notice what caused it. With rough stones people were tapping regularly and gently against new porcelain objects. In order to apply scratches to the glaze.

Decorating vases.

The word glaze derives from glass. It is not only just as transparent, it is at least as hard. For example, tooth enamel is the hardest element of the human body.

Glacing

In Asian workshops the term antic finishing is commonly used to describe that the customer wants things to look somewhat old. In that case

Porcelain is more likely to break than to wear off. A better evidence of age should be the so-called patina, the outer - layer which is caused by time and use as a skin on the surface. But porcelain remains largely pristine - all the more if it is regularly cleaned.

The patiently applied scratches were to break through the glass-hard armour, the glaze. Lest an arsenal of chemicals, dirt and grease could be applied to it...

Père d’Entrecolles: 'After it has been fired it is boiled for some time in a very fat broth, and after that it is placed in the foulest sewer where they leave it for a month or more. When it comes out of this sewer it passes for being three or four centuries old, or at least of the preceding dynasty of the Ming, when porcelain pieces of this colour and thickness where highly esteemed at Court.’

I once read that written Chinese doesn’t really speak of counterfeit, copy or reproduction but that the relevant characters rather mean reinterpretation.

Anne Farrer from the British Museum apparently read the same. ‘When the copying ceramist was a great artist, his reinterpretation had an intrinsic value.’

‘There is no doubt that the Chinese are naturally brought up to respect antiquities; nevertheless one finds that there are some defenders of modern work,’ Père d’Entrecolles writes in the first of his two long lettres (1712 and ’22).

'Old porcelain may be adorned with some Chinese characters, but these do not mark any point in the history; thus the curious can only find a style and colours, which they prefer to those of our time.

I believe that I have heard it said in Europe that porcelain, in order to have perfection, ought to have been buried in the ground for a long time; this is a false opinion that the Chinese ridicule. The History of Jingdezhen, speaking of the most beautiful porcelain of early times, says that it was so desired, that as soon as the furnace was opened, the merchants would fight over the first pick.

To De Waal the abundancy of imperial porcelain is too ostentatious. Under penalty of death it all had to be absolutely perfect, which smothered any whiff of creativity.

For instance, he reads that there is a record of an order for hundreds of shallow dishes for narcissi: ‘and I imagine walking down one of those endless corridors in the Forbidden City, a paced rhythm of steps and scent.

This isn’t about things looking nice, it is about things being correct. Sets are a way of controlling the world.

Mismatched, wayward porcelains would reflect terribly on your ancestors’ sense of the afterlife, just as much as a grubby tablecloth.’

Père d’Entrecolles heard of disasters concerning imperial orders as well:

The father of the current emperor ordered some boxes just about the size of the crates that we put oranges in; it was apparently for raising little red, gold and silver fish. This was meant to be an ornament for the palace; perhaps he also wanted it to serve as a bath tub, for, it was to be 6 inches thick with 4 inches thick sides. They worked for three continuous years on this project and made two hundred bowls, without one being usable. The same emperor ordered some slabs to be put in front of an open gallery; each slab was to be 3 feet high, 2.5 feet wide and 6 inches thick. None of this could be done says the Annals of Jingdezhen and the mandarins of the province presented a request to the emperor asking him for permission to stop this work.

On top of that, the gigantic numbers the imperial family were ordering for centuries.

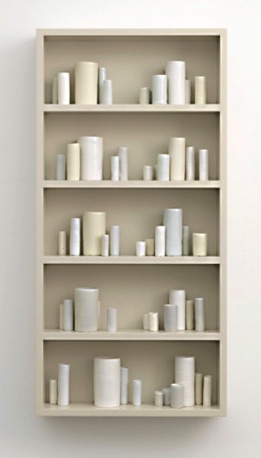

His own art - the price of which may reach a couple of hundred thousand - clarifies the last addition. Simplicity rather than numbers.

Besides being a potter, De Waal is a stylist, akin to traditional work from China, but to modern movements like Bauhaus (1919-’32) as well. He cites industrial designer Wilhelm Wagenfeld who, at the time, noted in dismay that ‘merchants and manufacturers laughed over our products... Although they looked like cheap machine production, they were in fact expensive handicrafts.’

Whoever wants to display simplicity, has to control the surrounding space. De Waal simply demarcates it. Without platform, simplicity exhibited in a busy, fast-paced world remains unnoticed.

With confinement and stylization an extra dimension is suggested, I suppose, a poetic layer that prompts silence and depth.

Any potter throws hundreds of pots, if not a few thousand, from lumps of clay. Nevertheless, it blows De Waal's imagination when he deciphers in the archives the imperial orders.

‘Surely they couldn’t break this many pots every year? I want to know where they are stored in the palace once they arrive on their journey from Jingdezhen. There must have been vast storerooms and endless inventories. There must have been rooms for the inventories. There must have been Official Counters of the Imperial Porcelain.’

Moreover, the hundreds of thousands of pieces of porcelain the Chinese emperors annually ordered had to be one hundred thousand percent perfect. Despite the enforced, immoral discounts.

De Waal gets to read the pages of last emperor Puyi’s (1908-12) porcelain inventory. The register, not written in court language but noted down in vernacular, turns out to be a mess.

‘There is someone counting in the room as this is being written. This page is recording losses: an imperial court trying to stem the daily flow of theft, the seeping away of prestige as objects disappear from room and storeroom. Nothing adds up in these pages of porcelain lists anymore.

The archive reports:

According to the guards Yong Kuan and Wen Mou, on the 11th day of the 10th month of 1908, the first storage room of the eastern quarter of Porcelain Store Number Five showed signs that it had been broken into. After investigation, it was revealed that sixty-six pieces of porcelain were missing, including fifty Kangxi marked yellow-ground bowls decorated with green dragons, six green-ground bowls decorated with aubergine dragons and ten Jiaquing marked

Li Deer’s gang, the porcelain thieves, got in by disguising themselves with the right kind of hat as officials.

The reply to the final order in name of the imperial five year old reads: ‘We received your letter, but we cannot fulfil a demand for one hundred seven-inch dishes glazed in sacrificial red. We no longer have the skills.….’

There is not even an apology.

And this is my Mao, master Lieu says. He has very, very long fingers that fly around as he talks and his eyes are hazel and wry. (…)

The Leader is young and tall. He is wearing sandals, one foot slightly raised on a rock, and his left hand holds an unfolding map. He looks engaged, and I realise that the reason this sculpture works, while thousands of others are choked by their symbolism, is that it is a sort of self-portrait. This is Lieu as Mao, a young man off to gain the respect of the world. - De Waal.

The very last ‘emperor' was mainly casted in porcelain himself. Mythological heroes and laughing Buddhas were no longer allowed – opium for the people – but Mao himself appeared in hundreds of thousands of busts and badges.

During the sixties, the party received the order to design a befitting porcelain gift for Mao.

Very quickly there was panic. The ten tons of raw materials were found to be insufficient and Red Guards were transferred to the project to speed up the refining. No one was allowed to rest and home leave was cancelled. Technical problems were judged as indicative of insufficient regard for the Leader. This is a crime punishable with death.

Then came the agonising decision about what they could make. Objects that were neither historicist (see what we have lost), nor scholarly (do you know what this unusual glaze is Comrade?). The porcelain could not be overtly decorative either. This was a revolution, so no vases and no goldfish bowls.

So it had to be useful and skilful and new: a tea set.

This is about young people, teenagers, whom Mao dictated the battle cry Smash all old things! – and who accordingly caused terrible suffering and irreparable damage.

Twenty-two kilns were fired over the next six months and two sets of 138 pieces were finally delivered to Mao’s compound in Beijing in early September 1975.

He approved.

A year later he died.

A dozen years ago, a young couple was selling it on a market just outside Beijing.

Apparently the vase was dear or useful enough to someone to apply iron clamps along the line of fracture to prevent the crack from turning into a complete break.

Perhaps family of the couple had recently died, people from the Mao era, for whom the vase was precious, if not indispensable during those lean years.

One would never discard such painstaking, time-consuming work, symbol of that needy time, I suppose, even when you can easily buy a dozen new ones.

On weekends most villages and towns in China traditionally have a small, bit-of-everything-market. Previously, these usually took place in an open field where people’s goods were displayed on the ground, whether or not on a rug. Along with the increasing number of people and economic activities during the past decades, these markets turned into serious commercial sites and many municipalities decided upon covering them and organizing them more strictly.

You will always find some new and used porcelain. On the bigger markets, merchants from Jingdezhen and Dehua are likely to be present with a large display.

At the sight of the adjacent heap of packaging materials – cartons, foam, paper, rope – this clumsy dishwasher instantly feels pity: overnight packing, loading and unloading, unpacking in the early morning chill, and packing up most of it again in the evening…

One day I’m standing in a crowded market, looking at the merchandise of such a potter. On the ground in front of him all kinds of small wares are on display. Behind him a dozen man-sized, decorated vases are shining.

Just like glass, porcelain may all of a sudden – sometimes years after manufacture – simply snap. Perhaps it was too rapidly heated or cooled when it was made; however it may be, too much tension remained. A cold draft, a high sound, a fly landing on the edge, who can tell what suddenly caused it.

A small vase then says pang! but the large vase behind the potter roared boom! and split into two pieces.

As if an old-fashioned cannon went off. The man and I both saw the forming of a mob that out of curiosity shuffled closer and closer. Powerless, we foresaw the disaster that was about to happen.

Gradually, the people in front were pushed forward by those in the rear. On the outer edges his displayed porcelain was being trampled. Shouting or stopping the crowd was useless.

Resolutely, the potter picked up the two parts of the large vase, raised them with arms stretched over his head and walked smack into the crowd. The sharp shards scared the people back and split the crowd in front of him. All eyes followed the clearly visible chunks of porcelain and all bodies turned along with him… he saved the rest of his porcelain.

- More pictures taken in Jingdezhen on this site:: hier en hier

- Well made documentairy from 1981:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3ckTvhBAg4

- De Waal at work: https://vimeo.com/50611081Gl

21 dec. 2015 18:51

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty

in hope and credulity, in promise and lie. And you could end up on the scaffold, as once happened in a German sovereign state, with a sign above your head that read: ‘If only he had better learnt to make gold.’

undoubtedly the toxic fumes that he inhaled for twenty-five years played their part.

After his death no one could make sense of his notes.' - wikipedia

‘These changes are not worked out by mineralogists or chemist but by potters adjusting one batch of clay to create a special run of objects, working out why these stem cups have warped, or responding to a hike in prices from the clay merchant.’

so little. I’d watch the colour of the kiln change from reds to oranges to yellow to a searing white. I was by myself.’

court at Versailles. There is to be an auction. New stuff from China. – De Waal.

the amount of work that has gone into it and the result. The thimble-small cup and saucer with a view of Potsdam, courtiers, gilding, was pointless then and looks like they did it because they could.

just so plump and sweet and high-summerish. You can taste nothing, no bite, no acidity, just sugariness waiting for the plumps of Schlagsahne, that coating of cream. You can feel the boredom in the fruit painter; berry, berry, berry…

Actually as I force myself to look at it, it is precisely the coming together of late summer in the 1970s – holidays as a teenager, boredom, small cottage, brothers, endless plums, blackberries, compulsive rereadings of bad novels – that makes me realize this is passive-aggressive porcelain.

I feel certain this is a new category of porcelain.

I start a list.

In terms of material, labour and manufacturing a plate or image cast in porcelain is not outdone by a plate or sculpture in bronze. Yet the idea prevails that bronze is much more expensive - and it is, at the metal grocery.

Making it all the more difficult for Westerners to determine the date of a given piece.(…) In no other area of Chinese art do we see a conflict of connoisseurship as we do with regard to porcelain, in my view.’

Mr. Wong, antique dealer in Hong Kong, to Blumenfield:

‘If this piece is Song ding yao, it is very, very cheap, but if it is not, it is very, very expensive.’

‘wear and tear’ can be translated as refined damage.

Sometimes the client’s impudence stretches very far: ‘Demolish a foot of the statue as if it was ripped off its plinth during the night.’

Plunder as a sign of authenticity…

For the last, say forty years I have been trying to convince statue makers of the idiocy of this practice. You can make anything look old, you can seldom improve the quality. The only effect has been that they no longer frantically hid their Secret Recipe when I walked in, but conspiratorially laughed about it.

Edmund De Waal: Fake. Fraud. Ersatz. Bogus. Replica. Simulacrum. Counterfeit. Forgery. Sham. (….) As a teenager I pinned a postcard above the wheel in the studio. It was of a celadon tea bowl with a crackle as fine as a skeletal leaf. And I tried to make it again and again, hoping for the moment when it would come to life and cranes would fly out of it.

And not for a moment the kid wonders whether the bowl is ‘real’.

From that comment it is not to be supposed that these had been buried. It is true that in digging in the ruins of old buildings and especially in cleaning out old disused wells, one finds there, sometimes, beautiful pieces of porcelain which were hidden in times of revolution. This porcelain is beautiful because at such times people would only think of hiding what was precious, that they might recover it when the troubles were over.'

bowls with clouds and cranes. The guards on duty at the time were handed over to the Shen-xing-si Bureau of Punishment for supervision.

My favorite piece of porcelain.