Home

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty

Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

GESLOTEN / CLOSED

16 okt - 5 nov '25

Contact:

31-20 - 6 23 55 64

06 - 588 41 370

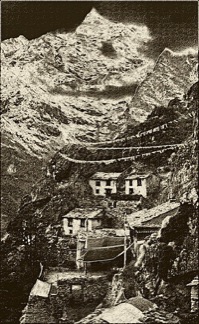

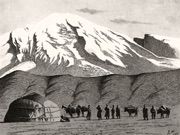

Spring 1730. For several weeks, Samuel travels with the caravan through the Nepalese middle mountain range. Traders and officials sometimes have pack animals. Most carry, each man for himself bent forward, their cargo and equipment in baskets on their backs.

Like a column of worker ants, the procession treks through the relatively young, sharp mountain landscape.

Regularly they have to descend deeply to cross wildly flowing water and then climb up steeply to recover the lost height.

Behind every mountain ridge the path turns out to swing along yet another valley.

Rarely is there a view of a settlement or hamlet, at times more tigers and other felines seem to be living there than people.

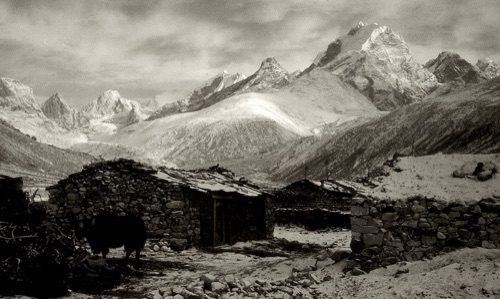

Once above the tree line, the path runs across a flood of grit and rock along glacier rivers. Every once in a while one of his legs threatens to slide away, occasionally near a ravine.

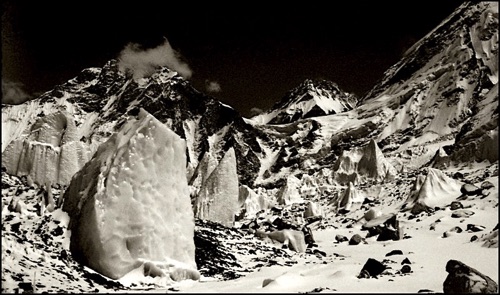

Once on the mountain pass, Samuel is astonished by the supernatural creation with perpendicular ice walls and boulders that seem to have been thrust upward by cubist ice pillars as a sacrifice.

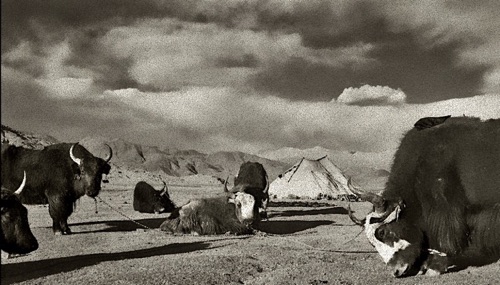

When snow falls, trails fade. Without any apparent worry the caravan guide seems to rely on an inner compass, but Samuel suspects that actually the imperturbably trudging yaks lead the way.

But then, after about four weeks of climbing, descending and climbing again, it is as if each caravan member with one last effort actually steps onto the plateau - and is finally able to walk upright again.

No longer is the view a next mountainside but a vast, unfathomable distance. The season is good: the sun is shining, there are no biting storms, in fact there is hardly any wind at all. From time to time the silence between two slopes is so absolute that it startles Samuel when a bird flies over.

Nepalese carriers return home, Tibetans take over the cargos. A lot of freight is transferred to yaks and donkeys as well. Whoever has money rents a horse for himself, but most of them continue on foot.

Behind them, at the horizon of the plateau, the Himalayan peaks slowly disappear from view.

Samuel re-reads the pages he copied in Patna from Desideri's travel records, but also the notes of all that was told or entrusted to him by the Jesuits and Capuchins in Nepal.

‘At the first morning light we get up at once. Usually we already smuggled our obligatory prayers into the night before. Together we take down the frozen tent and break the ice from it. As well as possible, we smash the canvas into folds. After that we bind the colossus onto one of the beasts of burden.

Before leaving we drink their salty butter tea. It must be good for something; they‘ve been drinking it for centuries. If you call it soup, you’ll get used to it. Everything warm is welcome. Moreover, it prevents their dry as dust tsampa flour from caking onto your palate.’

'You do not have to walk the weeks long distance, you can also buy a horse. But beware that you will be stuck on it all day long. That you will stiffen and go numb.

In addition, your horse must eat on the go. The more food must be taken along, the more pack animals are needed - and these have to be fed in their turn.'

'And the same goes for those who carry the coins to pay all the other carriers; they themselves have to be paid as well. Each and every day, mind you, there is not much confidence in strangers on the desolate plains.’

'For a horse a snowfall may prove to be too high or too exhausting. But even without snow they may drop dead on the way, even under your saddle. Or the animal simply cannot continue any further and is finished off on the spot. To serve as food the same evening.

Ten years ago we, two inexperienced jesuit brothers, began the journey from Ladakh to Tibet with seven horses. Only two of them reached Lhasa in the end. The one was so exhausted on arrival that it had to be finished off, the other one died a day later.’

Where there is no sun, Samuel notices, there is cold. When the path runs between rocks, his lower body feels frozen while his forehead beads in the mountain sun. The reflection on the white world blinds him. Sleeping is difficult because the afterglow in his eyes is painful at night. A fellow traveller gestures him to rub his eyes with snow.

It only helps moderately.

One morning, however, he notices someone braiding something from a few tail hairs of a yak and tying it in front of his eyes like some kind of elongated eyelashes.

A big improvement, absolutely, though still not as effective as the frames with cut smoky quarts that some rich people are wearing.

Every caravan member who sees frozen horse or other droppings lying on their way, quickly picks it up. Anything that may burn is taken along to prepare food and drinks in the evening, shared or not.

Samuel's bed is hard, a few sheepskins on the floor. Because of the altitude and the exertion he sleeps only for fragments of the night. But the prime culprit is all the vermin that travels along in his sheep's clothing.

Only in the midday-sun can the caravan members take their clothes off. Not to wash themselves along a creek – for their skins would soon turn into old rags – but to scratch and search. Around him the muttering of mantras appears to combine well with the crushing of lice and the like between thumbnails.

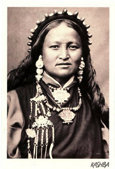

Virtually all caravan members wear a collection of amulets and talismans around their neck necks, on their back backs, in their hair or on their naked body bodies.

Some of the pilgrims among them are literally weighed down: buddhist figurines and clay tablets, tubes with written mantras, mascots of animal or human bone, herbs and lucky stones,

pieces of metal or stone fallen from the sky - in short, infinitely multifarious pleas to the cruel universe in the supposed language of nature.

On the way, Capuchins and Jesuits sometimes own hand copied parts of the Kangxi map of 1718. That’s how Samuel knows that Tibet must be about the same size as Western Europe.

So far it consists of empty plains with few inhabitants, mainly nomads.

To his surprise, however, the plateau attracts numerous pilgrims from extremely distant areas such as Persia, India, China – or Zeeland.

Domestic pilgrims generally travel in small groups. Together they leave their hearths and homes for a trip of a few years to legendary places of power.

They trek to mountains that connect heaven and earth. To caves where yogis became enlightened. To ancient temples

and monasteries where monks and lamas are the custodians of wisdom and secret teachings.

Together with some caravan members, he looks at a group of curiously dressed but very cheerful nomads. As best he can one of the Nepalese men explains that these families sold their houses one day to accomplish a pilgrimage to Lhasa.

Apart from a few yaks, they only took along some pots and pans. Now, two years later, they were on their way back and utterly happy. Not only had they been blessed for their next lives but also for their present ones, because only once had they been attacked during their trek; only one of them and their yaks lost their lives.

Pilgrimages without deprivation and penance apparently do not lead to salvation, at best to an occasional grand view.

Some years earlier, in India and Nepal, Samuel saw groups of wandering, half-naked men defying death by rubbing themselves on cremation sites with ashes of burnt corpses

Here in Tibet - where wood is scarce and the soil frozen - he sometimes sees people chopping the dead into pieces to sacrifice the lumps to the air.

That is to say: with the aid of some drumming and hooting, a few vultures obligingly arrive after a few days of flying.

During his journey through France, Italy, India and Nepal, Samuel regularly saw statues and chapels along the

way.

At this extreme altitude, dreams and visions and reality seem to blend.

Images in the midst of a sea of flames with twelve heads, gaping mouths, bulging eyes or a thousand-and-eight arms… it all seems to belong to everyday life.

Occasionally he regrets not having studied more theology during his university days in Leiden. The roman monks he meets on the way always receive him warmly, albeit with some reserve. The adventurous young man - whose nearly inconceivable journey commands respect – is, after all, from Calvinist-Protestant Zeeland and therefore a heretic.

A part of mankind prefers to make itself dependent on an authority outside itself. Upon seeing and sometimes experiencing the many religions and religious traditions, Samuel's own idea of God has been changing into mere questions these past twelve years.

So he knows better than to start a discussion with capuchins and jesuits.

They explicitly call themselves 'christian warriors' and don’t hide the fact that they have only come from so very far to 'combat the errors that confuse these people.’

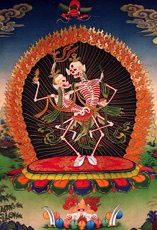

He sometimes sees dancing skeletons painted on temple walls, graciously grinning at him.

Life and death seem more closely intertwined on this thin-aired, almost otherworldly high plateau than he has seen in other cultures along the way.

Around temples, monasteries and shrines temporary markets regularly take place. Part of what is on offer comes along with pilgrims from the far corners of Tibet itself, but also from India, Assam, Bhutan, Mongolia or China. Whenever the caravan makes a more prolonged stop, that’s where Samuel can be found.

For a lot of exotica is traded as medicine, as an antidote to ailments as well as to the evil forces behind those ailments. But spices, dyes and chunks of stone have Samuel’s attention as well.

He scrutinizes everything, occasionally buying something.

Meanwhile, people nudge each other. They follow him and mumble: who is that blue-eyed eccentric with that ruddy beard, does he possess healing gifts?

As always, Samuel keeps a close eye on the very last moment for ducking away.

Also on the roof of the world, spring gradually dawns. Some days the caravan even treks through one of those Shangri-las with green plantings and budding fruit trees - they are the enclaves that provide nomads with barley, turnips or peaches, in exchange for cattle or wool.

Usually, however, long journeys towards Lhasa usually cross completely deserted plains. It is the century in which Holland has less than two million souls, the former world power Spain some seven million and Tibet even less than a million.

Only returning groups – on their way to Nepal or India –occasionally bring some news from the capital.

From Desideri Samuel had already understood that surrounding countries – such as Mongolia – and tribes of the Eurasian steppes – such as the Dzungar Khanate – repeatedly invaded and plundered Tibet with brutal force.

For several years, however, a Tibetan man named Pholhane has been able to keep all the native and foreign parties apart.

Perhaps it’s not so surprising that after a century of unrest he managed to establish some order

and peace.

As a youth Pholhane chanced to be taught in monasteries of quarrelling orders. Like Capuchins and Jesuits they fought each other for power and the correct interpretation of the scriptures.

Later he became an official and then a judge. Until he switched to the army. Within a few years the ruling tyrannical leader appointed him general.

After the assassination of the tyrant, the regent Pholhane manages to work his way up to ‘king of Tibet’ by concluding an alliance with the mighty Manchu emperor in Beijing. After the treaty, Chinese soldiers remain stationed in Lhasa and the endless highlands are constrained and bordered. Tibet becomes a de facto satellite state of China.

(It is this agreement with which 'the very last emperor' in 1950 legitimizes the invasion by his red army.)

Once in power, Pholhane banishes the 7th Dalai Lama from the capital. In itself a risky manoeuvre, because the Potala, housing the beloved Kälsang Gyatso, is the heart of the country and its people.

To Pholhane the problem is not so much the young man himself, as his father – a guileful political schemer who continuously cultivates unrest and strife between the monasteries and Lhasa’s rich elite. For the first time since long, Lhasa and thus Tibet experience a long period of peace and security.

(As many dictators before and after him, Pholhane will not able to train a suitable successor.)

From conversations with capuchins in Nepal, it is clear to Samuel why Desideri had to leave his beloved territory in a hurry after five years. The fanatical jesuit did not only get into conflict with his capuchin brothers but even with papal Rome about whose domain Tibet was.

Also the hospitality of the Tibetan clergy and government cooled off considerably in the course of his five-year stay.

Or as regent Pholhane expressed it in a letter to him:

‘Despite the fact that we do not know your religion, we give credence and pay respect to all religions, ours and yours; moreover, in the past we have not slandered it and we do not slander it now.’

As the only one of the brotherhood, however, Desideri understood that the many statues and paintings in monasteries and ghompa’s were not idols. He understood that Buddhism was not a religion. For every 'warrior of christianity' the greatest enemy reigned here: atheism.

He studied the language and the script, and with his discussions he slowly but surely antagonised the spiritual as well as the secular elite. Consequently, Pholhane is more explicit in a second letter:

‘Despite the fact that you were of no use for us, not even worth one ounce of silver, we have nevertheless protected you with amicable sympathy so that neither harm nor injustice shall befall you.’

Thanks to the mediation of an Armenian merchant, the small group of capuchins is housed in Lhasa in a three-room floor of a building that belongs to the government.

However, Samuel prefers to keep his distance. Desideri already labelled the capuchins as well-meaning yokels, even though that may have been merely envy, for brother Della Penna had been a well-trained nobleman back home.

The Italian and Portuguese brethren are dedicated go-getters indeed – otherwise they, like Samuel, wouldn’t be among the first ten Europeans to reach Lhasa – but they are nevertheless rather narrow-minded.

As the caravan approaches Lhasa, a Newari trader with whom he got befriended, points at a lower mountain outside the city.

‘Chagpori,’ he says meaningfully – for by now he knows where Samuel's interests lie. At the top is a monastery that clearly has only recently been completed. It is entirely devoted to medicine.

On the recommendation of the Newarese trader, he finds a simple accommodation within the Nepalese quarter of the town.

'For how long?’ the landlord asks. ‘One or two months?’

‘Hm, maybe a little longer.’

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty