Home

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty

Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

GESLOTEN / CLOSED

16 okt - 5 nov '25

Contact:

31-20 - 6 23 55 64

06 - 588 41 370

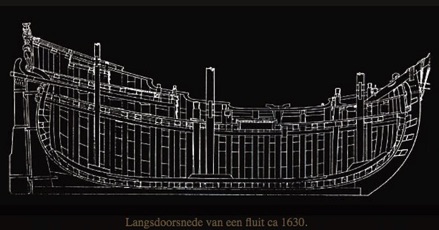

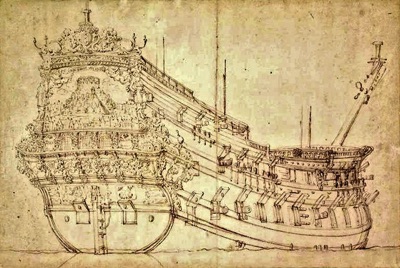

On the deck above the wide butt end of the ship Samuel has a small cabin for himself. After seven grand journeys between Holland and the East, the flute vessel is rather cracking and leaking.

It is time to sell ’t Hof niet altijd Winter, captain Koenrad van der Poel agrees, possibly for transport somewhere between the main Indonesian islands.

In addition to the comfortable lodgings at the stern for captain, chief navigating officer, chief merchant, ship’s surgeon and comforter of the sick (a shepherd of souls without theological training), about one hundred and fifty seafarers and soldiers are lodging in the part in front of the mast.

With their sea chests and hammocks they live next to or on the crates, chests and cannons between-decks.

Also the food is very different on the upper and lower deck. Per group of seven men, the workforce is usually given one container with food that is generally too salty and too fat.

On voyages longer than three months, vitamin deficiency gives rise to scurvy. Accompanied by poor hygiene and general filthiness, this gives rise to diseases such as typhus, dysentery or the maddening beriberi.

After departure from Holland - yet even before Cape Town has been reached - about ten percent of the crew dies, mostly among the soldiers from the poor German or French inland.

The launching of the bodies into the water sometimes occurs somewhat prematurely to prevent possible contamination.

As soon as Samuel appears on deck, the crew nudge each other. The renowned passenger with the reddish beard and Indian clothing is a colourful distraction. They heard that the silly customer rejects all meat and fish. Incomprehensible.

He doesn't eat much besides a little rice with vegetables. The daily allowance of

The days the ship sails through the Strait of Malacca, Samuel begins to understand from conversations with the captain how very much the company has changed since its founding, when his father invested part of his pirate capital.

Even since his stay in Cochin, admittedly some twenty years back, a lot seems changed. Possibly he has that impression because he himself saw and experienced so much more in the meantime.

The big difference with the English company – where Samuel prefers to stay, if possible – has come from the EIC allowing private trade, the so-called country trade.

For the VOC board, on the other hand, everything that company-servants and seafarers earn on the side is smuggle trade by definition.

To counter this, the management sends out tax inspectors, i.e. friends who hand out fines and confiscate the smuggle profits.

To subsequently share these with the very same board members upon return.

Samuel notices how suspicious the crew are among themselves. ‘Most of them do some

That is why the VOC is dependent on intra-Asian buying and selling. Sugar and textiles are profitable but voluminous.

Pepper and other herbs are light in weight but are hard to monopolize.

More than twenty years ago, the Heren XVII sent the message to all its fortifications and factories that landtraveller Van de Putte should be received and assisted properly on condition that he would not engage in any kind of trade.

'Private trade is forbidden. Yet it is one big tangle of self-interests,’ the captain sneers. He relates how the rulers and representatives are living in unprecedented abundance and wealth.

‘They have even created a code of law on ostentation. With every latest fashion, the list is lengthening.’

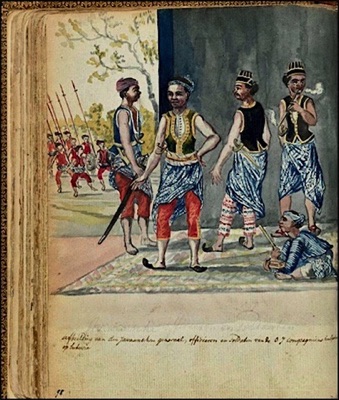

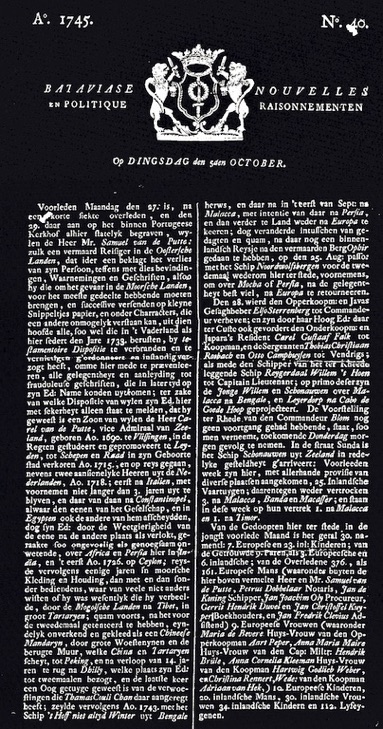

The law states precisely which rank may wear what finery. The Bataviase Nouvelles publishes regularly how many gold buttons, rings, bracelets or ornaments may be worn on cap or hat.

‘The fines are not to be sneezed at, but the beau monde take them in their stride– most likely wearing calf leather boots with silver clasps.’

Samuel recognizes the description. In Europe at the Hooghly River the

‘As governor-general Valckenier tried to do something about the abuses. Not much and not in a rush but nevertheless something. Council member Van Imhoff, however, torpedoed each and every measure. So Valckenier eventually put him on a return boat.

But Van Imhoff managed to get the Heren XVII in Amsterdam on his side. With money and promises, no doubt. As the new governor-general

'Bad is your policy usually according to those who lost out on it,' Samuel remarks, that much understanding of the company’s doings he has acquired by now.

In Bengal, Jan Sichterman – the director who named his fort after his boss Van Imhoff – had already told Samuel 'in confidence' that Valckenier was an incompetent, very incompetent colleague.

Van Imhoff

Captain Koenrad explains that when the sugar price dropped, Valckenier applied the old and tried VOC recipe: he had a large part of the plantings destroyed. Scarcity would naturally cause the price to rise again.

When the price unexpectedly shot up within two years because the competition could not deliver or transport due to bad weather, neither Batavia could.

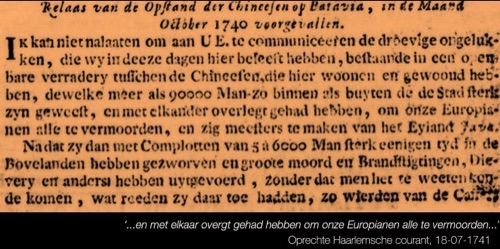

The destruction of the plantings, however, caused major unemployment and unrest among the Chinese migrant workers who were still crossing the South China Sea in junks and by now formed half of the population in and around Batavia.

It never became clear whether this had been the deliberate aim of someone behind the scenes had, but on October 8 and 9,1740 the ‘Batavian Fury’ took place: a massacre during which ten thousand Chinese were shot– the VOC after all, had better weapons and the experience of using them.

Subsequently, the sailors and underlings plundered the rich Chinese houses and set fire to entire neighbourhoods.

On October 12, the fire expired and The Chinese Murder was a historical fact.

The Chinese Killing 1740

Since many shops and workshops were no longer there, acute shortages arose and prices skyrocketed.

And, of course, the quarrels over who had to take responsibility within the Council of the Indies lasted for years.

Willem van Haren, member of the Batavian elite, shortly afterwards wrote the lines:

Death lives on the streets of wild Batavia:

For child nor greybeard Christians show mercy.

All that is just Christian, starts killing with joy;

And Java's stream, which first so gently and mildly sprayed

These places rushes angrily to the recently quiet roadstead

And spews the dead into a frightened sea.

Captain Koenrad keeps still and Samuel asks himself in silence whether it was a good choice to embark. All these years Batavia had seemed to him the farthest point on his horizon, a self-evident end-of-the-line. Likely, he was bound to sail back home from there.

Captain Koenrad guesses his thoughts.

‘Don't worry, the Chinese Murder was three years ago, things have quieted down by now.’

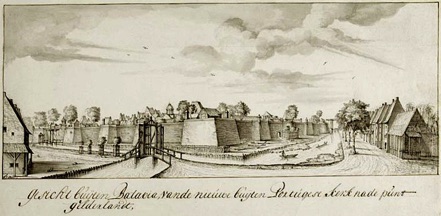

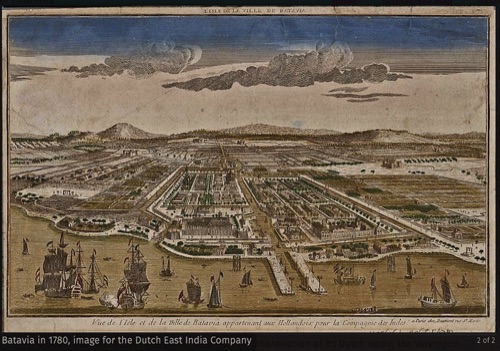

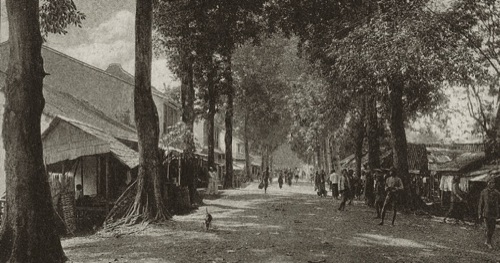

Batavia turns out to be a stinking little town with some four thousand 'white and half-white VOC-servants’, but due to local accretions and births, even for the company itself the workforce continues to be a mere guess.

The sugar mills - inside and outside town - consume large amounts of water. The ditches and canals become heavily polluted by their waste water. Recent earthquakes prevent the muck from finding its way to the open sea.

Immediately upon arrival, Samuel feels he can only get sick here, a large number of its residents had good reason to go and live higher up in the hills.

On his way to Tibet and India, Batavia seemed an ideal place to stay for a longer period and finally start working on his notes and journal.

He expected to arrive at an important maritime crossing in the farthest East, a port with a lot of experience and knowledge about the surrounding countries.

However, Batavia turned out to be little more than an inbred kingdom focused on territorial power to impose taxes and percentages and to organize cheap slave labour.

In the street the renowned landtraveller is viewed with curiosity and admiration. Samuel can knock on any door and talk with whomever he wants.

However, he rarely finds response, hardly anyone has a worldview even remotely resembling his. The only thing that seems to interest people is how he will monetize his experiences and discoveries.

He only pays the obligatory visits. With so much illness and mortality about, Samuel experiences, one needs but very few abilities to succeed in one's career. Not infrequently officials in key positions are at least in-laws of one another.

Sometimes he comes across well-known names from his former Zeeland and once even a fellow student from Leiden. Yet he now feels more like a stranger among his compatriots than in all the cultures of the past 27 years.

At the same time he wonders if he will ever come home anywhere. He does not really want to think about it – and so he thinks about it every day here in Batavia. Home is wherever you feel safe, he tells himself, where you dare close your eyes.

The bodhisattva idea that home is the expanding circle within which loving responsibility is self-evident, as it was taught in Tibet, did not reach him.

Twenty-two years ago, when he parted from his friends in Constantinople, he had moved on alone out of mere curiosity. To ever stranger cultures in ever farther away countries.

Slowly it dawned on him that everywhere wishes and fears in essence amounted to the same thing: safety and security. The thing, however, he could not reconcile all these years was why people everywhere were constantly battling one another. The horrible things that people do to each other everywhere.

Life, it seemed to him, is something that takes place between two wars - unless you trek away from them.

Particularly on the Indian subcontinent, he observed that to live is to suffer, but he did not see much difference between karmic resignation and calvinistic predestination.

In Tibet he observed that knowledge constitutes the essential difference between buddhist compassion and christian mercy, but daily life was just as bloody and threatening there as anywhere else.

In China, he observed that one’s own responsibility rarely extends beyond one's own family, one's close surroundings, but personally this did not mean much to him.

Here in Batavia, however, he is startled by how violent, greedy and cynical his own people have become.

Does he really ever want to go back to those premises at the Dokkade in Vlissingen,

On Sundays he sometimes visits one of the many churches. Mainly to prevent any disapproval and backbiting. The services strike him as strange. For the past twenty-two years he has been traveling among peoples who did not know a god or on the contrary hundreds of thousands at the same time - which he thought amounted to the same thing.

En route, the temples, rituals, festivals and other spiritual expressions had always amazed and intrigued him. After all his travels across vast plains under immeasurable celestial vaults, he now keeps all supernatural possibilities open.

For why would he limit himself to one god, let alone the One God of the reformed, protestant, lutheran, evangelical, calvinist, nederduits reformed church here in Inner or Outer Batavia?

Holding a small bible in his hands, he observes from one of the backbenches. He knows that the College of Deacons,

Occasionally he comes across books at a VOC-office or at someone's home. Due to ants, beetles and silverfishes, preserving a book in the tropics is as difficult as preserving a loaf of bread.

Especially the few travel journals have his attention.

The drawings on the cover usually speak for themselves: palms in a desert, five-headed snakes in a jungle, and so on.

‘Probably they’ll later describe me in similar terms,’ he realizes with a smile. ‘As an old emaciated man with a red pointed beard, clad in colourful caftan, pointed shoes and, why not like this, with a string of gems, a few clasps or, godforbid, a diadem on an actual turban.'

Samuel remains in Batavia for almost half a year. Not to get intimate with the Dutch community, on the contrary, but because he is unsure whether he will travel home overseas or once again overland. In both cases, the risk is equally great and unpredictable - a few years ago no fewer than eight return boats perished within one season - but the journey overland will evidently take much longer.

On the day that for the umpteenth time some company servant enquires after his maps and journals, Samuel cuts the knot and decides to travel back overland.

As long as the road continues, he does not have to think about arriving home, editing his journals or starting a settled life. He is neither in a hurry nor homesick.

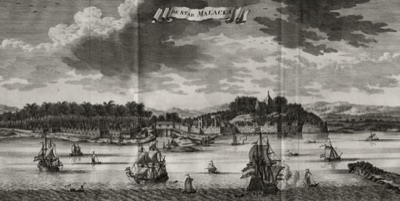

Not much later he embarks for Malacca, the major transshipment port above Singapore. A lot of Batavians have come to see him off –diversion is rather limited in their little town. Some even proposed to organize an official goodbye for him, with great ceremony, but that was considered

Upon arrival, it turns out that Samuel gets on well with the said sub-merchant and his wife. Claes de Wind and Catharina Altheer have been living in Malacca for about seventeen years and have no intention of ever returning to Holland.

In contrast to most VOC-officials, their interest does reach further than just the coastal area. They have contacts that regularly trek into the interior. If he wants, Samuel may immediately join an expedition that searches for unknown herbs and raw materials on mountain slopes.

The proposal reminds him of the trips he made with the novices of the medicine monastery in Lhasa twelve years ago.

He does not think twice.

In the early spring of 1744, when the heat isn't yet so intense, they set off. First eastwards to Ledang Gunong, a 1790-meter high mountain which they scanned to the top for herbs.

Then the expedition heads north for a few months, towards Thailand, to an old and barely accessible rainforest with monkeys, tapirs, rhinos, tigers and other animals unknown to him.

After some time, however, it turns out Samuel is not attacked by the big animals, but by the little ones that crawl under his skin and the tiny ones that find their ways into his intestines.

Fever and diarrhoea become chronic, they wear him out. No measure or medicine seems to provide relief. He is worried and wary. From experience he full well knows that he has to make decisions in time – even when they are untimely and annoying – because he has to stay ahead of exhaustion.

Together with one of the carriers of the expedition he returns to Malacca. Claes and Catharina take care of him as well as possible, but soon wonder aloud whether he’d better travel back overseas. After all, he is no youngster anymore, certainly not when counting the travel years of travel ahead.

It is mid July, it is hot and humid. Samuel is tired and agrees for Claes to try to arrange a boat to Batavia, because it's from there the return boats leave.

Once on board the Noordwolfsbergen, he again passes long mornings and afternoons staring over the water of the Strait of Malacca, the South China Sea and the Java Sea respectively.

He pictures himself coming home in Vlissingen and murmurs: ‘L'histoire se répète.’ Did father not go ashore after his fiftieth as well…?

A month later Samuel, sick and weakened, stays at the home of Pieter Lammens. Pieter is from Kloosterzande, not far from Vlissingen, a member of the Council of Justice living in Batavia for about nine years.

Pieter makes an effort to get the famous country traveler to stay with him, it will benefit the standing of his house and himself.

Tired as he is, Samuel puts up with it

After a few days, Pieter comes stops by to enquire after Samuel's health, even though he can see for himself that things are not going well. Soon he brings up Samuel’s fascinating journeys and what he actually intends to do with all his notes, maps and journals.

Samuel is silent – and remains silent.

'I have connections with publishers in Amsterdam,' Pieter suggests.

Samuel nods politely but notices that he feels old next to the young and cheerful Pieter.

He knows how publishers embroider the content, twist it and come up with exciting adventures for the sake of better sales. The way they claim, if need be, that the journal was written by a dying soldier or a silly ship boy, as if they could not fantasize.

‘As well as with publishing houses in Vlissingen, you know, I can take care of all of that in due course.'

Samuel's breath stopped short for a while; can it be that the young man is hinting at his passing away?

'If our Van Linschoten had not been so smart as to secretly copy and publish the Portuguese journals, our companies would never have been united,' Pieter laughs, ‘and the VOC would never have gotten this far.'

Again Samuel falls silent. Not haughtily, but wretchedly. He can well imagine what the VOC would do with his maps and notes. On numerous coastlines he witnessed their presence in recent decades. The christian VOC would urge other, armed parties to enter the pagan interior. Not even pretending to convert, but to get the wares he had described in his journal.

Standing legs spread in front of Samuel, Pieter wonders whether the sick man is listening or drowsing. Anyhow, the assignment to address the issue has been accomplished. He leaves and doesn't bother him further.

It is late September and also this late Sunday afternoon is quiet, hot and humid. Samuel lies in the guest room, for days he has hardly been about.

Two Betawi servants sit or sleep in front of his door, but he rarely needs anything. He snoozes, dreams or gets lost in strange thoughts. Occasionally he wakes up and suspects that he has been audibly delirious.

Then, his law of survival resurfaces: act before you may no longer be able to. He summons up his strength and gets up.

On the veranda, the two servants hear his thumping and rush to his aid. Samuel points at his saddlebag and stumbles outside, to the courtyard at the back of the house. He assumes kitchen timber will be available there.

After having arrived with difficulty, he asks them to build a fire pile. One of the servants notices Samuel leaning heavily against a wall and brings him a chair.

Once the stack is well lit, he points to the bag. The men understand what he is referring to, but hesitate. Samuel pushes himself up from his seat to enforce his wishes.

Then it dawns on him that the men disapprove of throwing a good leather saddlebag into the fire. With a limp arm gesture, he indicates to just throw the contents into the fire - they may have the bag.

As soon as his notes and journals are burning well, he drags himself back to his chamber. For a moment he seems to lose his balance, but the servants catch him and support him. For the first time in years, tears are flowing down his cheeks.

In the guest room there are some more papers, maps and labels lying on a side table, but it does not bother him, he cannot muster the energy any longer. After seven difficult steps, he lets himself fall onto the bed.

The next morning, Monday, September 27, 1745, Samuel van de Putte, aged fifty-five, reaches his ultimate destination.

a liter of beer or a peg of gin, is left untouched as well. His lordship only drinks boiled water with a few drops of lemon.

For his part, Samuel observes in amusement how the comforter of the sick reads out the obligatory prayers in the morning and in the evening and sings the psalms on Sundays, whereas on this trip between Bengal and Batavia predominantly Indians and Chinese stand in roll call on deck.

smuggling on the side,’ captain Koenrad explains. 'In Holland, they received for instance a pouch of coins or silverware from rich citizens who had their cutlery or dishes melted down.’

Because the company cannot sail on Spanish Manila, it has no grip on the load of silver coming from Mexico and Peru - the common means of payment in Asia.

The smaller the better - silver, pearls, precious stones or art objects - but for these precious things you need to have expertise and high-ranking relations.

That is why, right under his cabin, the butt of ’t Hof niet altijd Winter is half filled with opium - officially, at least.

behaviour often was equally extreme, although the stories seldom floated down the delta. Everyone, absolutely everyone, was involved in some illegal business or matter.

he returned to Batavia and at once shackled Valckenier. He has been locked up for about four years by now, I wonder if he will ever be released.’

Not long afterwards, angry hungry gangs marched the environs of Batavia.

The Dutch colonists panicked and soon paranoia swept the city. Van Imhoff proposed to ship all undocumented Chinese to Ceylon, whereupon the latter concluded that they were going to be dumped into the sea.

which, if all is well, will still be in his name?

The Batavian community seems solely focused on gain. Everyone is looking for opportunities to return to Holland, China, Java or elsewhere with big booty. They are only interested in the hinterland if they can get something out of it.

Not that they will go for it themselves, much too dangerous, they will send out local intermediaries.

paid for by the VOC determines who may preach or roar from the pulpit.

Amused, he looks at the local community, the majority of which consists of 'Christianized free and un-legitimated Indo-European Christians' who hardly know any Dutch, let alone church language.

to be too great an honour.

However, Samuel was handed a letter of introduction for a company man in Malacca who would help him on his way. Being renowned sometimes has its advantages.

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty