Home

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty

Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

Contact:

31-20 - 6 23 55 64

06 - 588 41 370

‘My stock is over there, right at the back,' the fleamarket trader points out.

- The place that used to be Fofana’s?

‘Yeah, but he has been dead for half a year.’

- What? Fofana is déád!?!

‘Sorry, didn’t you know? Was one of the first here with that African stuff.’

- Well, rather one of the last.

Back in the sixties there had already been African pedlars who came to Paris-Brussels- Amsterdam to sell antique or antique-finished beads, bronze articles and woodcarvings.

Especially in the beginning there were wonderful, striking characters among them. One of the first – as far as I remember –

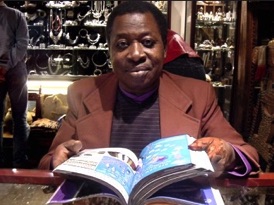

Fofana Sankoung from Kumasi, Ghana, born in Gambia.

Half of the year he collected wood carvings, beads, bronze sculptures and what not on the African west coast. The other half he tried to sell his wares in Amsterdam-Brussels-Paris: from shop to shop, to private customers, on the Queen’s Day free market and so forth.

As the years went by, Paris became too remote for him – as did Brussels, ultimately. Maybe the competition was too strong there because of so much more African immigration.

Still into the new millennium Fofana had the knack of finding people who looked upon poor Africa with a warm heart and who had some room to spare. Either for storing his wares, or for his bed.

For a long time he had a place somewhere near the Nieuwmarkt, with someone who used to be in Africa himself for long stretches. Then there was a basement in the Jordaan, and after that half a year in an anti-squatting arrangement.

With a tray from the cheapest take-away Chinese besides him and the BBC coming out of a creaky transistor-radio. But he was not complaining; maybe not-being-there appealed as much to him as being here.

But with the disappearance of the so-called humus-layer, there was no room left, even for him, in the ever more expensive inner city.

‘Go there. Straight, straight. Now there. No, there!’ It always felt strange that a man from Kumasi should be telling me how to drive from Amsterdam to Den Ilp on a Sunday morning. Somewhere in between the former farm houses he could use part of the top floor of an enormous barn for storage.

In the end, Fofana himself was to become one of the last of a generation of African pedlars who bravely risked going to Europe on the off chance.

That was not such a good idea. He did have much room for his wares, but it was too far from Amsterdam to take things along on a daily basis; after all, he had to drag the bags and suitcases with all his stuff in and out of the bus.

Gradually, things went awry: he kept investing more than he sold. The quality declined. Financing stock, as it is called nowadays, then threatens to topple the entrepreneur.

At the same time his children were growing up costing ever more money and a third woman joined the household (possibly because a brother or a cousin died).

‘You have to give me some money, Ton.’

- Yeah, doei-doei (as he always said when taking his leave), why?

‘Because you live here, you have a bissniss, you are rich.’

- Mister Fofana, you have a house, a big car and three wives… who’s rich?

‘My house is a hut, my car an old Chevrolet that drinks too much and believe me… three wives only make you crazy.’

By the way: small wonder that when Ais introduced him to his brother, he enquired as a matter of course: ‘Same mother?’

With his numerous offspring – swarmed out from inland villages to the inner parts of New York City – the paterfamilias did not have an easy life.

One day, during the nineties, his fleamarket cell phone starts ringing while he is sitting next to me. He yells a short conversation with Africa. Afterwards there is a short silence, but then: ‘You must buy something off me! My son needs money.’

- You haven’t had anything I would want for years, you know that.

He just walks out of the door only to come back shortly afterwards with a bunch of glass necklaces that I, sure enough, do not want but buy all the same. He takes the money and the metro out of the city centre. Somewhere in an internet shop he turns over the whole sum.

Within half an hour he is back sitting next to me and his cell phone rings. His son has cashed the money in Kumasi. I am bowled over. Transferring money to India or Nepal took me 2 weeks back then.

Those last years Fofana did not really understand the trade any more. That was also caused by the rapidly declining interest in African arts and crafts. These days there is hardly any specialized shop left in Amsterdam.

He stayed in bed later and later, kept putting on weight

Next day he came in, all smiles. To pay the dentist, he said beaming, he had first gone to his storage to fetch some woodcarvings. Maybe he could use them to pay the bill.

After the treatment he showed the dentist the objects in his old suitcase. The dentist threw his arm around his shoulders, took him into his private quarters and showed him… an enormous collection of African art. Of course he had a warm hart for poor Africa.

‘Ais, ask me why.’

- Wait Mister Fofana, please, wait a minute.

A moment later: ‘Ton! Ask me why, Ton.’

- Yeah, hold on, just a moment.

And after a while: ‘Ais. Ais!! Ask me why!’

- Okay, Fofana, why?

‘Well, Ais, now that you asked me why, I will tell you.’

And then he started a long, long argument leaving the others wondering in silence if this happened to be some old village-storytellers’ trick.

Been dead for half a year, the fleamarket trader had said. Some six months ago Fofana called me from Ghana, something he never did: too expensive, the rich white man should call him. It was a busy Saturday afternoon.

- Hallo? Who? Mister Fofana? How are you?

‘I just call you to say goodbye.’

- What? Eh, okay. Goodbye....’

And he hung up.

No idea what that was about. Let alone that I realised that the generation of African ethno-traders had come to an end.

Farewell Fofana…. doei-doei.

In 2006 Mister Fofana was pictured on the frontpage of the ministry of foreign affairs monthly, lugging a suitcase through the Staalstraat, on his way to Kashba. He was very pleasantly surprised.

30 jun. 2012 00:02

was a long dark whirlwind from Dahomey or Ouagadougou, in any case, he spoke French. He was convinced that if one wanted to sell to women, one ought to begin by courting madame! To put this into perspective: his tactics differed considerably from the grey tradesman-with-suitcase of the day. Typically, his courtship ended by chasing madame! round the table. Anyway, that usually also led to a quick sale.

In the eighties people such as Mister Musa came onto the scene: a relaxed Kenian loosely resembling an elderly Morgan Freeman with small glasses. His negotiations were accompanied by deep, almost grumbled sighs such as only older black men can produce ànd place. With such a dignified man who was actually too elegant for all that vulgar negotiating stuff… you would not even try to bargain…

The last time he came to sell – in the nineties – his sighs were deeper and sorrowful. His eldest son was dying of aids, somewhere in the Congo, as he had learned in Paris from other traders.

‘A friend of mine met Mister Musa in Nairobi the other day,' Fofana gravely told me years later, ‘he doesn’t trade any more, now he is just religious.’

and his health began to fail. One day he came in just before closing time with an acute toothache. For weeks, a visit to the dentist had seemed too expensive, but now he couldn’t bear it any longer. I gave him an address, through the medical switchboard.

We will miss him, the director of the Ghana Handicraft Association, as we sometimes called him teasingly when he sat there silent behind his glass of tea. Patiently he listened to the conversations, he was not the discussing type. But as soon as a subject concerned him – as for instance western arrogance vs the islam – he started off:

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty