Home

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty

Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

GESLOTEN / CLOSED

16 okt - 5 nov '25

Contact:

31-20 - 6 23 55 64

06 - 588 41 370

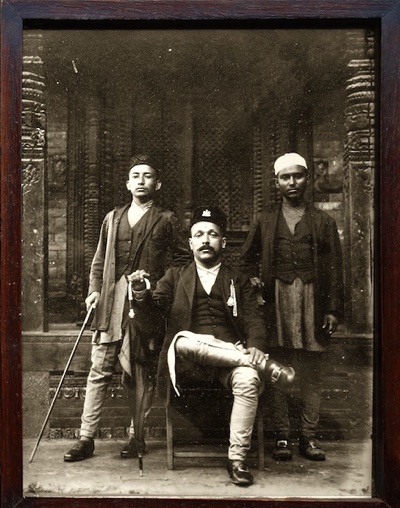

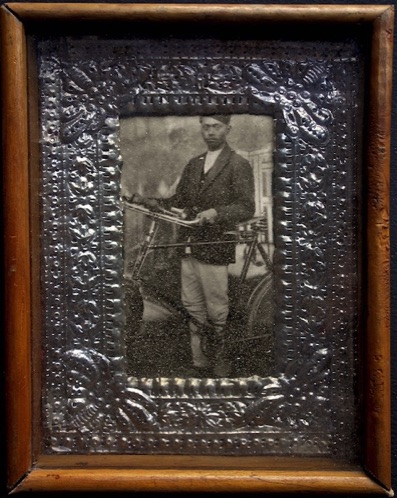

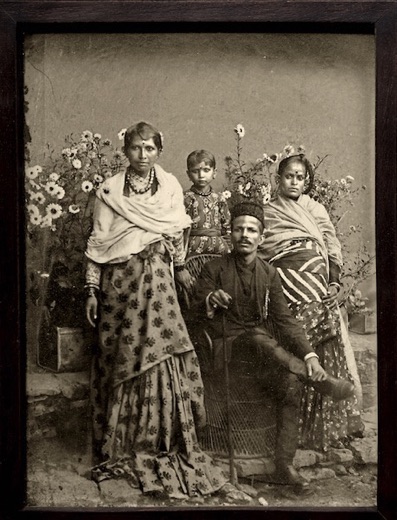

November 2016, old framed family pictures had been nailed to the palace wall. As if they came straight out of unknown living rooms.

They turned out to be part of a photo project in Lalitpur, Nepal. Of course, I photographed most of them, the chance to see them ever again, was too small. (See at end).

As poor and empty as Nepalese interiors in general were until the early 1980s, some family portraits usually decorated the walls. Often next to religious prints or hindimovie cut outs. The photographs could be surprisingly old, sometimes even dating from the nineteenth century. Remarkable, for how does a remote mountain state, closed to the outside world until 1951, happen to have such a widespread photo culture?

'British colonial policy was determined by British trade interests. While some countries expanded their own economy, other territories only needed to supply raw materials.

The Empire was kept together by shrewd politics according to the time-honoured principles of divide and rule, combined with keeping colonial economies dependent of investment and materials from the motherland.'

The administration of British divide and rule politics in India based itself on an old, already fairly diluted caste system, dating from before the Mughal Empire (1000-1750).

In an indirect way the British projected their own class society. Better jobs and limited say were only given to higher castes. This policy led in 1920 to a fierce rebellion. The British then shifted to an obscure form of positive discrimination, which emphasized the caste system just as much.

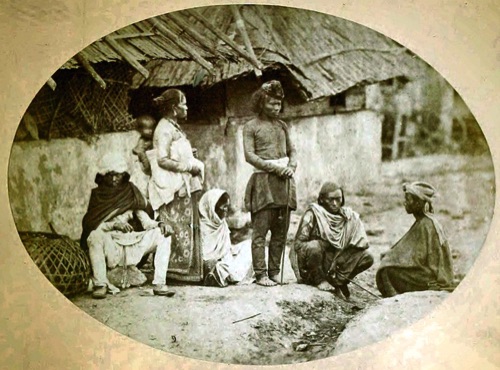

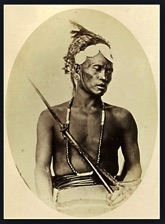

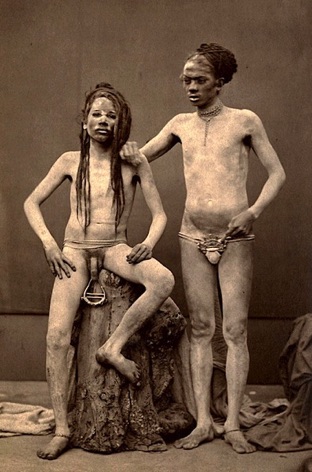

Bheels of the Vindyas’, India, 1862

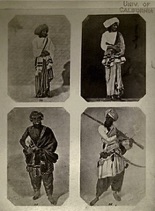

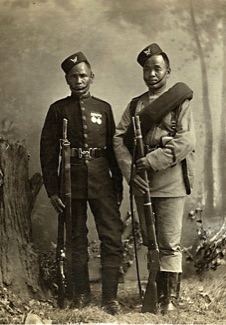

After the uprisings of 1857-58, the colonial occupier – army, commerce and government – wanted to improve their classification system by actually visualizing castes and ethnic groups.

Within the armed forces a request was issued to make use of ‘the new medium’ (in contrast with pencil and paint).

Soon after, a few cadets enthusiastically started to travel the vast subcontinent with glass plates, a toolbox full of chemicals, a black tent and two servants. They were rather sponsored adventurers than military spies. They were the very first generation of travel photographers, the early lensmen.

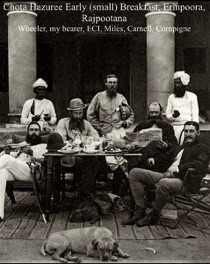

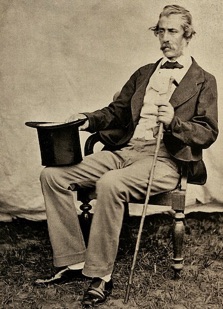

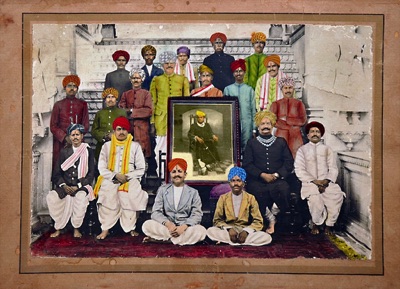

James Waterhouse, standing second to the left. Addiscombe cadets, 1859.

Officially it was said that photographs were being collected as a farewell gift to Governor General Lord Canning (left).

Not much later, in 1861, Her Majesty's Government requested the army men to provide more pictures. ‘For ethnographic study.’ Twenty copies per photo - an absurd order. To successfully take one picture on sun-drenched plains or high up in the mountains in itself was already a small miracle.

Another year later, again an official call for images followed. ‘For the London International Exhibition.’

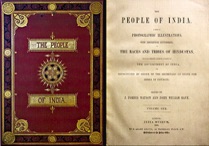

On the basis of 480 glass plates, J.F. Watson and J. W. Kaye eventually composed eight volumes under the title of The People of India, published by The India Museum in London between 1868 and 1875.

Watson’s official job was to create markets for British produce in the colonies, while Kaye was working at The India Office's Political and Secret Department.

Their approach was not new. Earlier Watson had gained experience with the publication of The textile Manufacturers and Costumes of the People of India, an 18-volumes edition of 700 textiles.

'The issue was meant to stimulate British exports to India. Watson argued: ‘For to cloth but a mere percentage of such a vast population would double the looms of Lancashire’.

‘As Watson realized, however, British attempts to export textiles to India were founded on widespread ignorance of Indian requirements.’ - John Falconer

A few attached photographs ought to change the lack of interest of manufacturers and show them how Indians actually dressed themselves.

The people of India

The photographs in The People of India are significant because ‘common man’ was portrayed as well (picturing women often was simply too complicated). A few years later, when the photographic process became simpler though not cheaper, for many decades only the elite was still pictured.

The 480 glass plates show barbers, blacksmiths, carpenters, charcoal carriers, farmers, fishermen, horse traders, teachers, beggars, merchants, officials, priests, warriors and water carriers and so on. Occasionally portrayed with utensils, religious objects, tools or weapons like bows, clubs, shields, rifles spears, and so on.

The accompanying texts are ‘very uncomfortable reading in the postcolonial era.’

The Smithsonian Institution, that shows the eight volumes on their site, makes such a cautious reservation that almost becomes insulting itself:

‘Please note that some language in this collection may be culturally insensitive or offensive to some viewers. (…) The social and political relationships detailed here are inextricably related to the complex realities of international trade and the history of the British Empire.’

‘Educated Indians were unimpressed with the outcome and with the general undertone that their people had been depicted both unfairly and dispassionately.’ - wikipedia

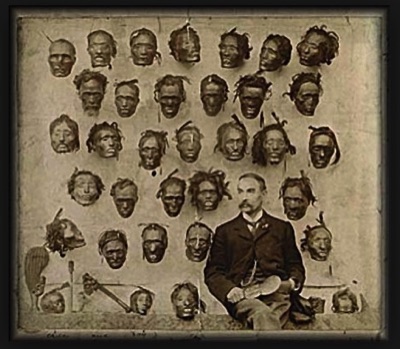

To facilitate classifying thinking, detachment is one of the first conditions.

Nepalezen in The People of India

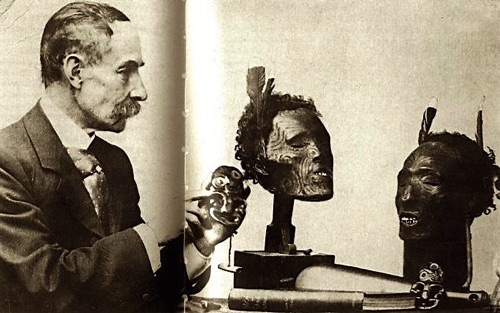

Major-General Horatio Gordon Robley (1840-1930), Maori skulls.

To facilitate classifying thinking, detachment is one of the first conditions.

‘When an historian, for example, is poring over a nineteenth-century manuscript, it is undeniable that knowing the identity of its writer is very helpful, if not vital. The background and personality of the writer will also help in weighing up the significance of what is written, as well as putting it into some kind of historical or social perspective. Photography is no different.

– Terry Bennett

With passage of time, the context, the world-of-then when the picture was taken, dilutes. The more you know, the more you see.

Naga, Assam, India.

Given the vastness of the subcontinent - plains, jungles, mountains - quite a number of young starting photographers got involved with this new military department. One by one adventurers on whose lives one may now endlessly click through online.

Young men like John Murray, Eugene Clutterbuck Impey, John Nicholas Tressider, William Simpson, J.C.A. Dannenberg, R.H. DeMontmorency, E. Godfrey, W.W. Hooper, H.C. McDonald, J. Mulheran, G. Richter, Shepherd & Robertson (later: Bourne & Shepherd), B. Simpson, B.W. Switzer, H.C.B. Tanner, Henry Ballantine, Clarence C. Taylor, James Waterhouse, etcetera.

Because of their activities, the first photo

By passage of time, each picture becomes more interesting. After a hundred and fifty-five years the People of India has become even more interesting. No matter how controversial its history and how biased the selection and captions, the collection is unique and informative because the pictures are the very first taken of India and its people.

Impey, Abott, Carnell.

‘The typical camera at that time was a heavy wooden box fitted with a fragile glass lens. A pristine glass plate would need to be evenly coated with a wet-collodion solution and then sensitized in a darkroom with silver nitrate. The glass plate was then carefully inserted into the camera and the lens cap was taken away to expose the plate to the view of the lens had been pointing at.

‘If any photographing had to be done we generally arranged to start it as soon as possible after sunrise, about 6, and finish not later than 9, when the hot wind would begin to come up. By that time also, the carts with the tents would have arrived, the camp be pitched and all ready for breakfast. During the day, perhaps a little printing was done, negatives varnished, chemicals prepared and so on. Not much camera work was done in the afternoons, the air being still too hot for work in the little developing tent, and the light also fell off very much after 3 or 4 o’clock.’

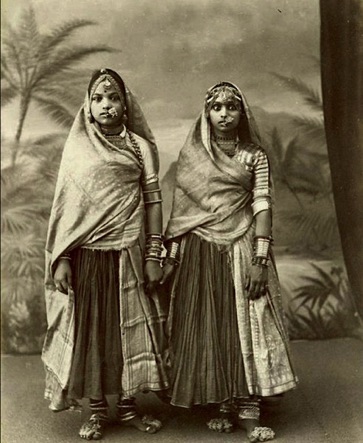

‘Meenas’, India, 1862.

The position of the sun determines the shutter speed. After three pm, it increasingly takes more minutes of complete standstill. Temples and landscapes could still be recorded but portraying people became impossible.

Incidentally, it is one of the reasons why no one ever laughs or smiles in those days. Not even a grin can keep its credibility for minutes.

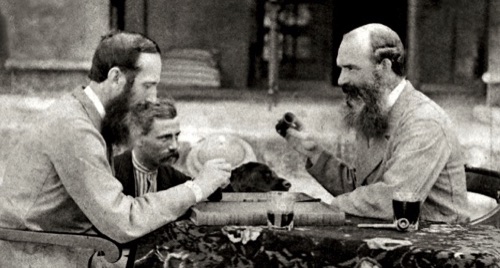

Some people, though, show happiness even when they don’t mean to. Or as friend Olga commented on the photo below:

‘Warmhearted bears are of all ages and of all cultures.’

‘Bheelahs’ 1862, India.

Glass plate 394 from The People Of India: Nawab Umrao Dlhu, Bhopal, India, 186

James encountered all kinds of other problems.

‘In these parts it was custom to begin the day with a draught of an infusion of opium, which was poured out by and drunk in the hand of a friend as a compliment. There were, no doubt, climatic reasons for the custom (as well as against intestinal cramps, worms, pains, pleasure and superstition) and the feeble old Rajah could do no business till he had his morning opium.’

It was not easy for James to get people in front of the camera. They kindly promised to sit but failed to show up. The reason being, the fear that a piece of your soul or atman was stolen. Another reason no doubt was that many did not want to dance to occupier’s pipes.

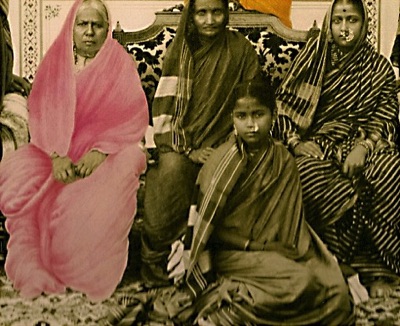

In many parts of the subcontinent photographing women was close to impossible.

Mawari women, ca. 1870, India.

The Begum was a thoroughly loyal and enlightened supporter of our rule under very great difficulties (the 1857 uprising) and I have a very kindly recollection of her personality.’

Apparently, collaborating with the occupier was the only way for the Begum to preserve her principality.

‘Madame Doolan, Shah Jehan and Begim of Bhopal in marriage costume,’ 1862.

As in India, common man and woman weren’t photographed for decades after. They could not afford it and those who could, were only interested in themselves and their quasi modern, European lifestyle.

Eearlier, resident Ramsey predicted that there would be no animo whatsoever for photography in Nepal.

‘Local rulers prefer coarse, brightly colored canvases, painted for them by local artists.'

Perhaps his brain had little stimulation on that lonely outpost because he could not be more wrong. On invitation, numerous European photographers made the trek to Nepal - all included - to immortalize the elite and their palaces, at least on photograph.

C.C. Charles

In India, British photographers had set up chic photo galleries to lure the local beau monde to the studios. Simply because the equipment and props got heavier and bulkier.

In cities as Calcutta, Bombay and Delhi salons like Bourne & Shepherd, Herzog & Higgins, Johnston & Hoffmann, or G.W. Lawrie & Co were opened.

However, for the Maharajas among their clientèle - who often sat bored stiff in their walled and pompous palaces - they were happy to make an exception.

By photosalons in India.

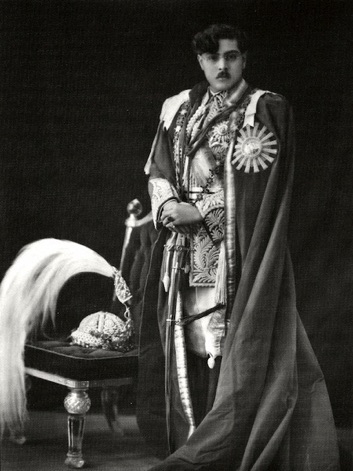

Soon enough, even rulers realized the impact of pictures as a business card, as an official portrait, as a propaganda tool.

King Tribhuvan Shah did see something in German politics of the thirties.

Just one of these chic photographers was the Danish ‘baron’ Richard Gordon Matzene. At regular intervals he started on a world trip and photographed the elite clique in India, China and Nepal. After three or four years, he returned home with countless references and art treasures to Ponca City, Oklahoma (where The Matzene Art Collection is presently housed in the local library).

Rana kids, Matineze.

Photographing in the streets was tried but was often a bit awkward and complicated for these studio professionals.

Pratyoush Onta: Ballantine describes the image of Kalo Bhairub in central Kathmandu as the most hideous object he saw or photographed – an unmistakable god of death that might well stand to personify cholera.

Hanumandokha, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Before adding that while taking the photograph of Bhairub, he and his team was 'surrounded by an inquisitive crowd that almost crushed us and our camera in their eager curiosity.'

The scenery photographs taken by Ballantine contain nothing spectacular and those of the common folks are only slightly more interesting.'

'The large hunting expeditions by the Prince of Wales in 1876 and Lord Curzon in 1901 were photographed by the hired firm Eastbourne and Shepherd ‘and their work is more interesting. But little has been published of what is undoubtedly still located in some British archives.’

King George V at lunch during a hunting party in Nepal in 1911. ‘His camp along the Rapri River counted ten thousand servants.’ - Ranas of Nepal

Rani Dibya R. Rana

In 1850, Prime Minister Jang Bahadur Rana dared to visit England and France, together with his two brothers. Possibly the two were ordered to accompany him in order to avoid a palace revolution during absence, a fairly repetitive pattern in Nepal. For Hindus at the time a big taboo still rested on crossing ‘the Big Black Water'. At return they had to undergo ritual cleansing for months.

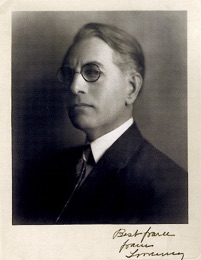

Jang Bahadur Rana by C.C. Taylor

Jang Bahadur’s numerous entourage counted a few artist as well. Upon return the palace interiors got more than just another type of wallpaper. Traditional art and decoration from India and Nepal was changed for a more European house style. The usually small, subtle, two-dimensional wall decorations made place for life-size portraits, hunting scenes and landscapes, all painted in perspective.

Jang Bahadur Rana, C.C. Taylor

‘In the palace of Dharma Shamsher in Hadigaon, Tangal, according to the 87-year-old Krishna Bahadur, there were at times between forty and fifty craftsmen and painters working under him. – Von der Heide.

Against pittance.

Still known is the story of a son who started his own photo studio, for the man in the street, soon earned a lot more than his renowned old father who his entire life applied carved, forged and painted art in the many rooms of the many palaces.

Interieur paleis Maharadja, India. Foto: Lala Deen Dayal.

Unknown is whether the Nepalese artists during this first tour through Europe got familiar with photography. Fact is that around 1881 Dharma S. Rana sent an art painter to the British photo salons in Calcutta for training and financed the purchase of a few cameras as well.

Foto: Lala Deen Dayal.

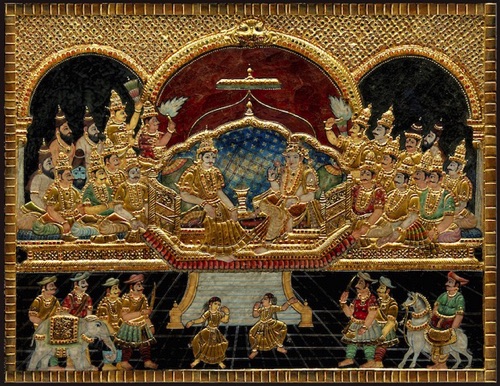

Zo boven, zo beneden, volgens de royalty. Thanjavur schildering, Zuid-India.

‘Apart from the photographs that were sent to their British friends, these photographs of the Ranas adorned their homes where they were mainly seen by other members of their fraternity. While reasserting internal Rana differentiation, these photographs acted to reinforce a collectively shared Rana sub-culture.’ – Mark Liechty

In 1937 liet de Nepalese generaal Kaiser Shumshere Rana zich in Engeland schilderen door de Hongaar Philip de László, 'een indertijd zeer populaire protrettist onder koninklijke en aristocratische families’. – Ranas of Nepal

Op den duur werden buitenlandse fotografen naar verhouding te duur en overbodig. Rond 1910 openden de eerste publiekelijke fotostudio’s in Kathmandu.

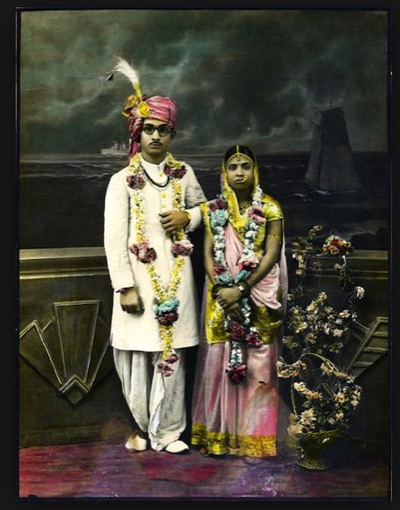

Evenals in India bekwaamden traditionele portret- en landschapschilders zich in het retoucheren en inkleuren van zwart-wit foto’s.

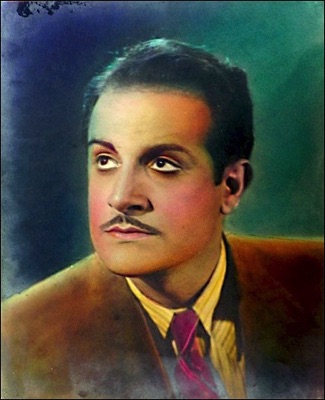

Deze foto werd tijdens een reis naar Europa in 1908 genomen en later in Nepal door Dirga Man Chitrakar ingekleurd.- Ranas of Nepal

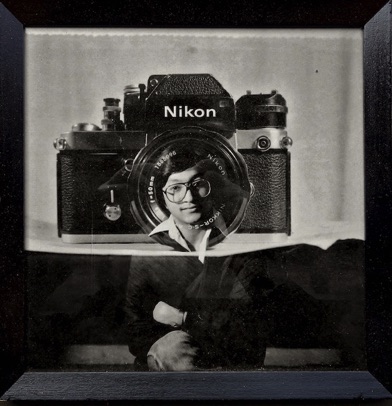

The wealthier clients requested the largest prints possible. To meet their wishes, one of the first photographers, Dirga Man, broke out a part of the roof of his house. The more light, the sharper the negative.

No cheap decision.

Most of the studios were at home, in a room with as much light as possible and a trompe-l’oeil on the wall as background.

With somewhere in front a small table or chair to suggest some perspective.

'Most studios were at the photographers’ homes, in a room with as much light as possible and a canvas painted background. With here or there a small table or chair for a bit more perspective.'

The first middle class people who have themselves immortalized, copy the postures of the aristocrats - be it without all the splendor and pride. Serious and stiff they stand still, even though it is hardly necessary anymore.

Above all they try to portray a life of religious devotion. Now that visual perpetuation is possible, they want to enter history as respectable ancestors. (Above)

‘Fakirs’, Westfield & Co, 1870-80. Betere benaming: Saddhu of Baba.

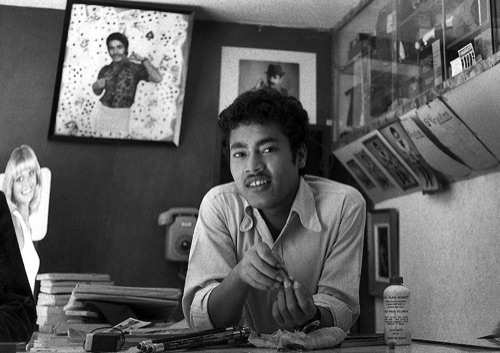

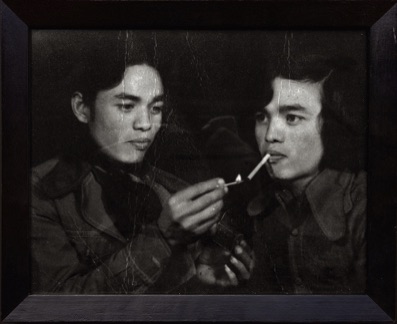

Once technology and logistics improved and the studios became cheaper, a new generation entered the studio and instantly the style changed.

Onta: ‘The subjects didn’t look at the camera; they smiled, laughed, played with props and shook hands. These poses were possible also because of advances in technology, as subjects didn’t need to sit still for long periods of time.

Chitrakar recalls mostly young people visited the studio around festival time, when they had new clothes.’

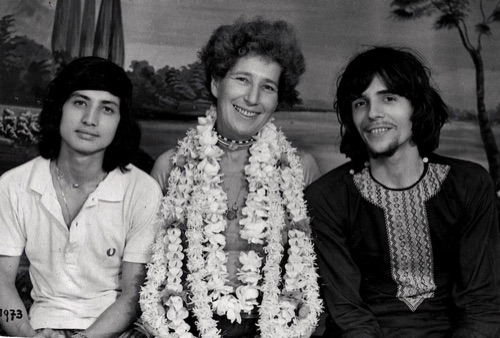

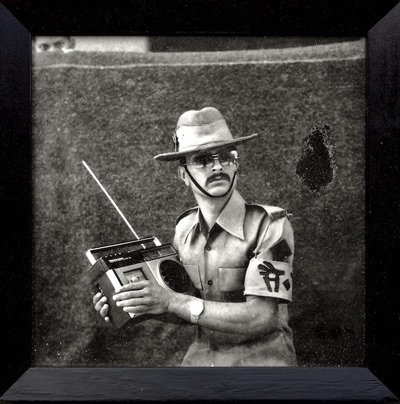

Bovenstaande jongeman van de Tuladhar Studio in Kathmandu nam in 1973 onderstaande foto:

Only around 1850, the first true negatives were invented in Europe: a gelatin emulsion with silver bromide carefully smeared on a glass plate.

Less than two years later, British soldiers photographed significant colonial buildings, areas and inhabitants in India, Burma and China.

Making light images was a costly and time-consuming affair, but a few departments were very willing to invest. For instance, to the British colonial army it seemed useful to have the colonies and its peoples photographed.

magazines were published in the colony and wholesale in the required chemicals organized. In order to be no longer dependent on information and of months consuming sea shipments from England.

‘About 1862 Mr. Lyell started a photographic depot at Allahabad which was a great boon to up-country photographers. His things were good and his prices reasonable.

In 1860, the Bengal Photographic Society had been in existence in Calcutta for about three years, but the first number of the journal was not published till May 1862. (After sufficient subscribers had registered).

The Society undoubtedly did a great deal in those early days to encourage the art in India, but in an out of the way place like Saugor, its influence was nog much felt and I did not join it till 1865.’ – J. Waterhouse.

Estimating the appropriate exposure time, which could be anything from a few seconds to a few minutes, was largely a matter lighting conditions, intuition, experience and luck.

The lens cap would then be replaced and the glass plate removed and taken back to the darkroom for further chemical treatment. The aim here was to ‘fix’ the image on the place, which then became the glass negative. If the process had been successful, then prints could be taken from the negative. But even this

printing required a significant degree of skills and dexterity.’

‘Apart from the camera and darkroom (a portable tent if traveling), he would need a tripod, various lenses, a large number of fragile glass plates, bottles of chemicals, and fresh water. These hard-to-get and relatively expensive chemicals would need to be mixed in the right proportions. - Terry Bennett (Photography in Japan).

James Waterhouse: ‘I had a convenient theory that a little white light did no great harm, if judiciously kept at a distance. Similarly, a little weak cyanide of potassium solution judiciously applied was good for cuts on the fingers. At the same time the abolition of cyanide from the dark room is one of the great advantages of the gelatine dry plate and present day work. One generally felt the effects of the cyanide sooner or later.’

Between the lines of his noted memories he sighs that on average one in five pictures succeeded and at times as many as nine plates of glass were needed to get one decent negative.

James' father was a lawyer, the family had no

relation to India. After completing school, he nevertheless enrolled for the Indian army and was trained at the military academy of the East India Company.

‘Here cadets bound for India received training in mathematics, fortifications, geology, chemistry, surveying and the other skills required for a military career in the subcontinent. Tuition in photography was also part of the curriculum at Addiscombe, where it had been introduced by the drawing master Aaron Penley in 1855.’ – John Falconer

James Waterhouse: ‘When I first went to Saugor the best place to get chemicals and materials was Calcutta, but it took almost as long then to get things up from Calcutta as it now does to get them out from home, and in the wet season,

when the rivers were in flood, cart traffic was almost suspended. We, therefore, often had to prepare such chemicals and materials for ourselves as we could, among them albuminised paper, nitrate of silver and chloride of gold, and in this way acquitted a very practical acquaintance with the work. I have always preferred to make my own chloride of gold when possible, so as to obtain the nearly neutral salt, giving a deep orange colored solution, which is better for toning purposes.'

‘I also prepared shellac varnish, obtaining the raw material by sending a boy up a pipal, or sacred fig. tree in the garden, the branches of which were infested with the lac insect. The seed lac so gathered, was broken off and well boiled, with, I think, a little alkali, till the lac dye was removed. It was then dried and dissolved in spirit, finally being passed through animal charcoal to clear it and lighten the colour.’

‘Her highness the Begum showed a most intelligent and friendly interest in the proceedings, and knowing the difficulty there was for a European photographer to obtain photographs of native ladies, she dressed herself, her daughter and some of her ladies in different costumes so that I could photograph them. In order, however, not to offend the Mohamedan prejudices all these photographs were taken in purdah, i.e. from behind a screen, so that I never actually saw my lady sitters but only photographed them, the lens of the camera projecting through the screen.'

Not very different from Nepal, where the elite remained in power by keeping the country closed off and the colonial power at bay by regularly providing a regiment of Gurkha soldiers.

On the government’s request from Delhi for photos of the locals – ‘all racial types’ – the former resident col. G. Ramsey (right) reacted laconically that no one in Khatmandoo could photograph, so they’d better send someone with a camera – and budget.

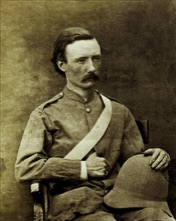

Clarence Comyn Taylor was the one delegated. As the youngest son of a British general, he was born in India. Serving at the infantry, he got severely wounded during the insurgency of 1857. He was transferred to the colonial Political Service. Two years later he had skilled himself in photography.

His first photos, taken in Rajasthan, were not that special, but his work in Nepal had so much quality that seven plates were selected for the last volume of The People of India.

As a result, C. C. Taylor (left) took the very first pictures in Nepal between 1863 and ’65. He did not only record monumental buildings but people of all walks of life as well.

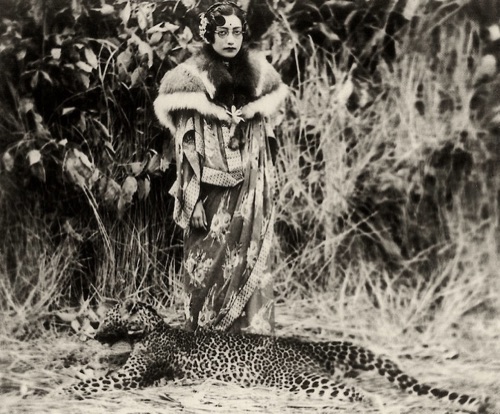

‘Nautch girls’, Edward Taurines, ca. 1890

(To keep control over the photographic material, the ruling families in Kathmandu organized photo studios within their compounds, the historian Onta notes.

He does not report that when color photography came up, these families were depending on local laboratories like everybody else. A few were owned by foreigners. Even if the palace messenger was standing near by, it must have been possible to make copies of sensitive material. Who knows in what archives this may still be located.)

Like all glass in Nepal, the panes had to be carried in baskets from the border with India, through the promontory, to the Kathmandu valley – a trek of ten, twelve days.

'The family still has an envelope with the imprint: Chakra Bahadur & Sons, Photographers to the Government of Nepal; Oil Painters, Photo Enlargers, Dealers in PhotoMaterials; Manufacturers of High Class Furnitures; TahitiTole, Kathmandu, Nepal. – Suzanne von der Heide.

Tibetan women in Darjeeling Studio.

vlnr. Rajas Tuladhar, Martha Diatlowicki-Cohen en ondergetekende.

In the thirties, the portable camera gradually came into use - and just as gradual the large number of studio’s declined.

Some photos of the project mentioned at the very beginning:

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty