Home

KASHBA Asiatica

Ais Loupatty

Ton Lankreijer

Staalstraat 6

1011 JL Amsterdam

Open 12:00 – 17:00

Zondag / Sunday 14:00 - 17:00

GESLOTEN / CLOSED

16 okt - 5 nov '25

Contact:

31-20 - 6 23 55 64

06 - 588 41 370

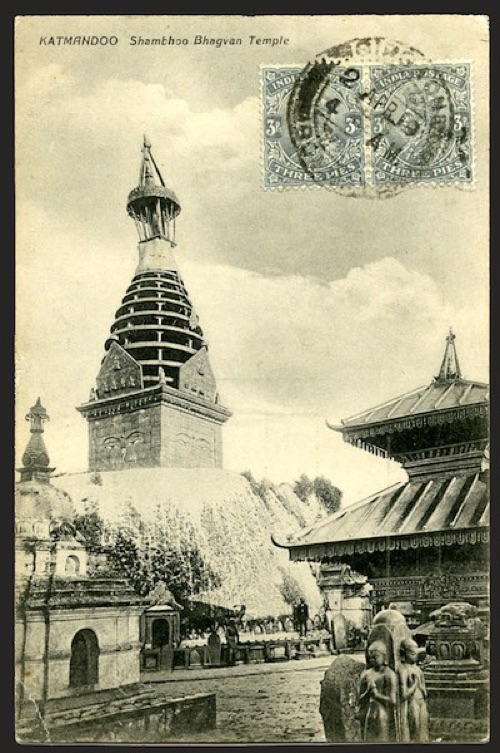

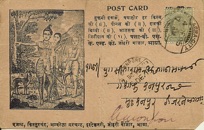

Recently I got this old postcard as a gift. Always nice to see an old photograph of a familiar place. Just as nice as finding answers to the many questions the card raises.

- Why did a postcard exist from a country that permitted no traveller to enter?

At the time the postcard was sent from British India, probably around 1900-1910, Nepal had already maintained a closed-borders policy for a century or so.

By annually recruiting several battalions of Gurkha soldiers for the British colonial army, the southern border remained undisturbed. And with the Himalayas as an icy northern border, the elite could remain rather carefree in the saddle.

A small, poor country had better not allow foreigners - other than bureaucratic envoys or professionals and entertainers to make life in the palaces more agreeable - to cross its borders at the time of The Great Game.

Even foreign dynasties were seldom invited any further than the promontory for hunting elephants, tigers and rhinos.

A closed-borders policy was the only defense for countries like Tibet and Nepal against the supremacy of better weapons and bigger armies of China, Russia and Britain.

In the time this card was sent, collecting postcards was a worldwide craze. Many households kept scrapbooks to preserve and cherish them. There were specialized magazines, trade fairs and travelling exhibitions of thousands of cards.

One did not have to have visited the photographed location oneself — these were the early days of travel photography.

Anything-elsewhere was interesting to see a picture of and to keep.

Map publishers sent out photographers to surpass competitors with yet a greater choice of highlights.

In 1910 a publisher in Detroit, for example, advertised with sixteen thousand individual views.

Local shopkeepers from remote villages in Europe sent pictures of their local scenery to the card publishers. After all, if a traveller visited their village, he was bound to buy several cards, since it was after all more interesting if you had actually been there.

The global collector’s mania came to an end during the first World War.

In 1861, the year the postal system started in India, the number of postcards without any image –– with only a short message –– at once ran into a circulation of millions. Together with 43 million letters and 4,5 million newspapers

It was the cheapest way to let someone know anything in your own wording without having to go there in person.

By the way: without the existence of a post office in the neighbourhood. No idea how this was organized, but I suppose the famous documentary about the daily collecting and delivering of home-made lunches — veg, non-veg, brahmin, etc

— to to some two hundred thousand students and office workers in Mumbai comes close.

After its introduction in India, the postcard was considered a luxurious version of the bare lettercard. Technically, publishers did not get beyond printed drawings initially —hand coloured or not.

A fine, imported picture of a significant passage.

With the exotic stamps forefront — philatelic postage — the card would be a desirable addition to any album.

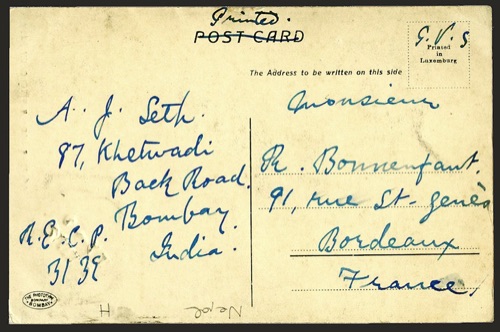

It seems a bit strange that the sender writes G.V.S. on the back, Gratuit Valeur Sceau, meaning free of postage — because the stamps are glued on the frontside?

Seth once was a title for money lenders in India, but has long been a ordinary name for Hindus and Jains. The Back Road address is nowadays located in an expensive neighbourhood. The address has been swallowed up by a company with multiple buildings. My lunchtime mail to a puzzles loving employee unfortunately got no reply.

- Why was a postcard from Nepal printed in Luxemburg?

The photogravure was properly developed by the Czech Karel Klíč. German printing houses, however, managed to perfect it for lithographic reproduction.

Due to their consistent quality, they were able to retain the postcard

Countries like Austria, England, France and Luxembourg printed a lesser quality but cheaper. Probably to keep the cards affordable despite the extra shipping costs, Indian publishers like The Photo Type Company in Bombay preferred to order in one of these countries.

- Why did they spell Kathmandu as Katmandoo?

None of my my native speaker friends had an answer to this. One United Stater assumed that oo rather belonged to exotic loanwords as voodoo and taboo. While he also thought it a bit childlike: oops, peakaboo, etc. Or as exciting place names in old adventure in travel books: Timbuctoo and Kalamazoo.

‘No native speaker will hesitate in pronouncing oo, but may do so with u. The u sort of hangs there at the end, as in Chengdu or Xanadu and would most likely confuse a 19th century Brit as to how to pronounce it: is it a long or a short vowel?’

Possibly the answer was determined in a heated meeting on May 28, 1872, when the British Colonial India Council chose the so-called Hunterian System out of a number of transliteration methods.

Right away there was a lot of criticism, partly because the system converts the script of India, Nepal, Burma or Tibet to Latin script according to the English pronunciation.

But it was necessary: in old books you may find hhhh in compound words, for example. The system took effect only gradually and evolved somewhat over the years.

The earliest transcription of Kathmandu is listed in the seventeenth century travelogue of the Jesuits Johann Grueber and Albert d'Orville: Cadmendu — as some United Staters pronounce it — remarkably with a u at the end.

Kathmandu is named after an ancient temple at the centre of the former village. This mandap was apparently built from the wood of a single tree (kastha), without the use of nails.

After launching the Hunterian System, the th character of the original Kasthamandap was anchored in the capital’s official name in Latin script.

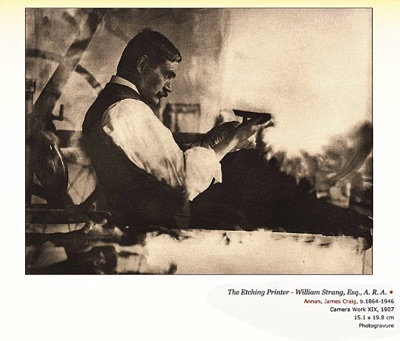

Who took the picture and when?

Until 1900 most photographic postcards for the Indian market were printed in Europe.

As the quality improved in India, publishers like Mizra & Sons in Delhi and The Phototype Company in Bombay sent their own photographers to all corners of the subcontinent.

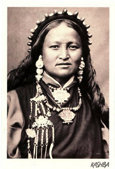

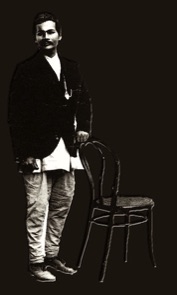

In 1850 one of the regular portrait painters to the Nepalese court, Purna Man , was invited to travel along with the prime minister on a state visit to Queen Victoria — and then on to other major European cities. Probably he brought back several cameras and chemicals, as his offspring was successful in photography for a few generations.

Bored and craving for modernity in the isolated Himalayan valley, the Nepalese elite wanted to be pictured with their pomp and palaces. Also to be taken more seriously by the wealthier maharaj families in India with whom they

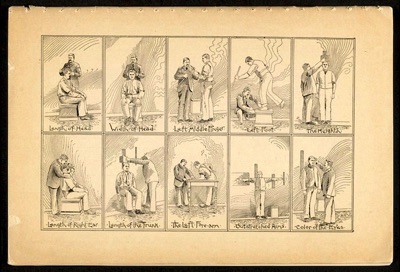

By the end of the nineteenth century the Western mentality of to measure is to know flourished— quite contrary to the Asian way of life.

Well-known are the anthropometric photographs showing white 'scientists' literally laying people along the yardstick as objects of investigation.

The British colonial government wanted to compile a photographic inventory of the many ‘tribes’ of India –– which was ultimately to result in a kind of encyclopedia named The people of India.

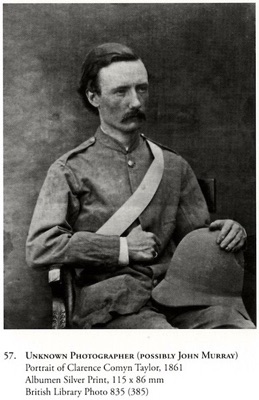

The mutilated soldier Clarence Taylor was retrained as a photographer and sent to Nepal. He turned out to be a true craftsman: a good eye for composition as well as skilled in evenly spreading the silver emulsion on paper for a single exposure.

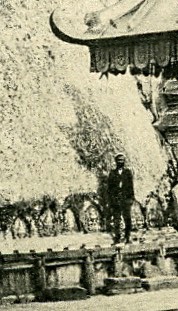

Was Taylor the creator of the Katmandoo photo? One of the men in the picture seems to be European — perhaps John Murray, a friend of the photographer?

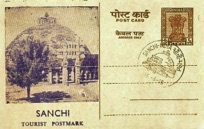

For centuries the Shamboo Stoopa had been half an hour’s walk from the city and then another three hundred worn steps to the top of the hill; the journey was part of the reflection.

Some of the many temples, niches and images may date two thousand years back.

The current shape of the Swayambhu temple complex was mainly realized in the seventeenth century.

After the monkey temple was in danger of sliding during a heavy monsoon in the seventies, Unesco reinforced the flanks of the hilltop with armoured concrete.

Once on top of the hill, the reward is vast and grand: sometimes overlooking a valley with the majestic Himalayan range in the background, other times the spectacle of a fantastic fight of threatening-thundering monsoon skies.

Buddhist site will certainly have appealed to the domestic market, even when the stupa was located far away in an inaccessible area.

British colonials, sailors and travellers bought and sent postcards to friends and family for their collections. Few would probably have known that Nepal was as closed as many parts of India and Burma where the British army would simply have denied them further

market during the first fifteen years of global collector’s mania. The majority of the seven-hundred million postcards sent in 1908 within the United States, for example, had been printed in Germany.

preferred to make arranged marriages — in order to keep the offspring listed in the highest caste-regions.

Obviously, the rulers also realized the effect of photographic propaganda in the form of ceremonial portraits in every public building.

Nevertheless, it remains possible that the first photographer in Nepal was a European. Maybe one of the scarce envoys or maybe even the seriously wounded soldier Clarence Taylor.

During the last decades the hill has been completely encapsulated by the capital. Fortunately my old postcard still shows something of the pastoral atmosphere in which the Unesco-monument was once built.

All photographs and texts ©Kashba Ais Loupatty & Ton Lankreijer.Webdesign:William Loupatty